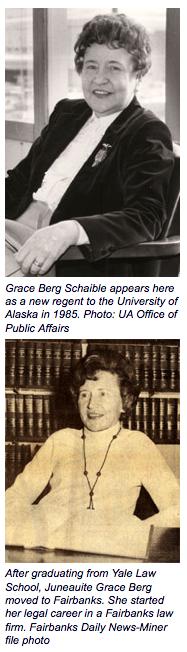

1985-1987 Grace Schaible

1985-1987 Grace Schaible

Fairbanks

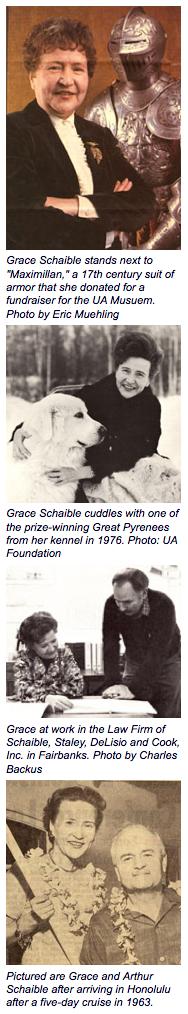

Grace Berg Schaible: Arctic Attorney

This profile of Grace Berg Schaible appeared in the spring 1976 edition of Alaska Alumnus.

"Don't enter college too sure of what you want," advises Grace Berg Schaible, a Fairbanks attorney, "because if a university is any good, it will expand your scope of opportunities so much you'll change your mind."

Since hers was not a straight path from Juneau childhood to U of A degree to the Alaska Bar, Grace knows whereof she speaks.

In seeking her own fulfillment, she has dreamed several dreams. The end result involved some compromise which a modern student might not have to face, but without intentionally supporting women's liberation, Grace is living proof that an educated, free and creative woman can be anything she wants to be, particularly in Alaska.

As a child, she played a family game--her Norwegian father picked a spot on the globe at random; Grace had to name 10 important facts about each place. As a young student, the legislature's activities each winter lured her insatiable curiosity. As a high school student during World War II, the issue of "peace" was heavy on her mind. She was at home in the outdoors as well as in downtown Juneau.

The logical choice of career was the foreign service, especially since she was anxious to travel and see the world. But after two years at the University of Alaska, she entered George Washington University to study the art of the diplomat, only to learn quickly that a woman would never be accepted there.

In fact, it seemed to be a career open only to men from a recognized prep school and Ivy League college who could bring along their own private fortunes. And it was a time when the State Department was considered subversive.

Second Career Her professors encouraged her to become a college professor, instead, based on her interest in Alaska history and political science. "Dreadfully homesick," she gave up the National Symphony and the Library of Congress—both fringe benefits of Washington, D.C. that make her eyes light up even today—and returned for her senior year at the University of Alaska.

Dr. Charles E. Bunnell, first president of the U of A, had recruited her as a freshman away from her job as secretary to the Superintendent of Juneau's schools and from Northwestern University. He welcomed her back and eventually put her to work as his own secretary, while she finished what she calls "an uneventful senior year."

During Commencement, as Andrew Nerland handed her a diploma, Dr. Bunnell also placed his hand on the document so that he could share in the joy of awarding it to her. She had been the Outstanding Freshman Woman; she finished as the Outstanding Senior Woman.

At Bunnell's request, she stayed on in Fairbanks to be secretary to the university's new president, Dr. Terris Moore. Then she "fooled around" for a year in a variety of jobs from a crab cannery to the Office of Price Stabilization before starting graduate school, again at George Washington.

"It was the only time I ever had a complaint against the University of Alaska," Grace declares. She had an unacceptable double major and spent a frustrating first semester filling in undergraduate history credits.

Her academic work combined with the family fascination for politics. It became a thesis entitled "Alaska Legislation During the Republican Period (as she adds, "of neglect") from 1921-1933." The paper was a study of the federal and territorial legislation in several major areas as it affected Alaska.

Working on the paper in the library at the state capital of Juneau, she often served unofficially as guide in the history stacks for former governor and later U.S. Senator Ernest Gruening, who was researching a book in the summer of 1953.

When her own work was finished, she received a call from the University of Alaska. Would she interview for a job with the Legislative Council, forerunner to the Legislative Affairs Agency? It was a time in her life when the irregular hours did not appeal to her; she gave them a "tentative no."

Not long after, Dr. Ivar Skarland and several other U of A scientists came through Juneau. Grace invited them to a big spaghetti feed which led to an evening of fine conversation and an admonition from Dr. Skarland.

"Not many women graduates of the University of Alaska would be offered a job with the council," Skarland scolded. His advice led to a "tentative yes," and then a job that soon fascinated her so much she gave no further thought to knitting, classical records, or the clock.

Research proved to be the love of her curious life. As she prepared background material for laws which the Legislature would consider at the next session, she also pondered where to go for her doctorate to get on with her plan to teach.

George Washington U. refused her, saying she had exhausted all their resources; Stanford University attracted her, but offered no study funds; Johns Hopkins came through with the much-needed funding, but wanted her to change to "Southern history," an unthinkable idea!

Then Grace discovered something very basic about herself. Even a Sunday School class of very bright junior and senior high kids didn't excite her. She didn't like to teach! Once again, her career prospects were up in the air!

Third Career?

Since she was so happy doing research, she considered jobs as a National Archivist

or a Navy historian. This led to fact No. 2—she no longer wanted a life outside of

Alaska.

In a job where she was constantly surrounded by lawyers, her goal finally became clear. The seed had been planted by Dr. Bunnell, himself a lawyer; there were half a dozen women practicing in Alaska already. The law seemed to meet all her requirements, both dreams and desires.

Looking to the Northeast for a school, she asked which one had the longest experience with women. Yale won the toss, though admissions were decidedly tough because Yale wanted only "women who were going to use their degree."

Entering in a class of 13 women, she became so sick she barely made it through finals the first term and finally quit second term, "hating the law." She returned to Alaska and "a desperate Legislative Council" preparing for a Legislature that created the Constitutional Convention and got Statehood rolling.

Her illness might have been partly psychosomatic, Grace admits, due to some personal distractions, but once back in Alaska, "I felt 100 percent better."

"There's one thing about Yale, though," she says, chuckling. "Once they admit you, they never let you go." Before long she was receiving letters from the registrar's office saying, "We trust you have not given up your intention to return in the fall."

Asking "What intention?" she returned anyway and enjoyed the hard work. That summer she served as a law clerk in Anchorage in the office of former Legislative Council head Paul Robison. She also discovered the joy of theater through director Frank Brink and the Anchorage Community Theater production of "The King and I." She actively supports the arts, and has traveled half way around the world to spend a week at the Viennese Opera House.

A small item in the New York Times told her of a tragic fire in Fairbanks that had taken the life of her favorite UA professor, biologist Druska Carr Schaible. (Both she and her professor had dated Dr. Arthur Schaible years before.)

A note of sympathy to Dr. Schaible rekindled an old friendship. On Christmas Day, 1958, they were married in the 5th Avenue Presbyterian Church in New York City. Liberated before her time, Grace went back to her final term of law school; the doctor returned to his Fairbanks practice.

In the summer they honeymooned and visited relatives—all in Africa, where Schaible was born. When they returned Grace went to work as a law clerk and knuckled down to study for the bar exam.

As Grace Berg Schaible—"the Berg to honor my father, the Schaible to honor my husband,"—she was the first person admitted to practice in the newly formed Alaska State Court system.

"For a woman wanting to practice law, Alaska is the place to be," Grace says enthusiastically. "There is no underlying economic or social prejudice," she says, excluding that of a male criminal who prefers a male criminal lawyer. She finds that many of her colleagues and classmates are envious of that fact.

Alaska is also "a good place to be" for the creative lawyer looking to turn over new legal ground. "We have a young, dynamic court system that is not encrusted with a 150-year old body of law." This is important, Grace feels, to a state with "a rapidly expanding economy which brings with it new problems and the need for new solutions."

Grace's own professional challenge at the moment, as a member of the firm of Merdes, Schaible, Staley and DeLisio, is the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation, headquartered in Barrow. Dealing in corporate structures and controversies, the laws of dissent and distribution (heirship), and similar matters, she has a growing fondness for the Arctic way of life.

The Arctic Slope Eskimos are land-oriented people. Under the leadership (Joseph Upicksoun), they are trying to follow a philosophy which will provide a economic development base so they can stay home and manage their lands. Moving into the Western business world with funds from the Alaska Land Claims Settlement, they hope to retain the very best of their own culture.

"It is easily stated," Grace says of their philosophy, "but difficult to accomplish." She feels the Arctic Slope people have been more successful in this respect than have some of the other native corporations.

"No person can go into the Arctic and operate as though it were Madison Avenue," she says, "but there isn't much adjustment for someone from Fairbanks."

She thinks the University of Alaska was good at preparing people for life in the bush when she was a student here. That is not its most important role now, according to the woman who has been an active alumni for many years and recently received a landslide vote for reelection to the Alumni Association Board of Directors.

"The University's role is to provide—as it always has—an atmosphere for knowing what can and cannot be changed, and for perceiving the difference."

She sees the "warfare between the Anchorage and Fairbanks campuses" as the element which must "be brought to a end before it destroys the entire University." Since the Constitution set the University apart as "a fourth branch of government," she objects deeply to the "route of dependence" which the Board of Regents has chosen in allowing the Legislature a line item veto of the University's annual budget. It's an issue worth fighting for in the courts, she believes.

"And you have to learn to play the political game—in retrospect, that's the way it always has been in the territory and the state."

Is the university capable of meeting the needs of postsecondary education in the state without competition?

"It can change and adapt, as most Alaskans can," Mrs. Schaible believes "We're all pioneers, living in a hostile environment. You can't compromise certain things, but you must be willing to compromise on others."

The university's first president, her friend Dr. Bunnell, "was a man who dreamed the impossible dream, but he was never ashamed to have a broom in his hand if the doorstep needed cleaning."

It's the approach the university should have—structure where it is needed, but responding in an ingenious, unstructured way where that will work best, says the petite brunette who cares greatly about her alma mater. "As for all Alaskans,' she says, "it's the only answer for survival."

John C. Sackett was appointed to take her place on the Board of Regents.

Grace Schaible is also mentioned in these articles:

UA Regent: Arthur Schaible

History of the Presidents' Residence