1965-1966 William Whitehead

1965-1966 William Whitehead

Juneau

William Whitehead Building honors a former doctor and his wife

This article originally appeared in the Dec. 12, 1997 edition of the UAS newsletter, Whalesong. Additional information has been included in the article.

By Eileen Wagner

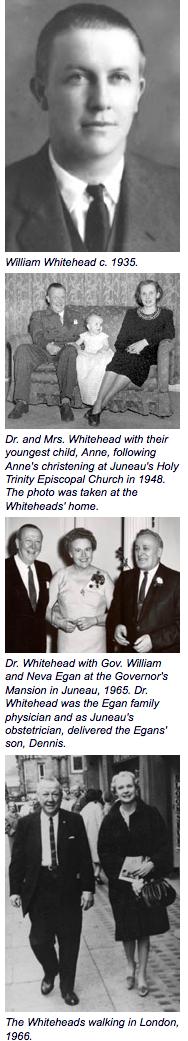

The moment Stuart Whitehead started talking about his parents, for whom the Whitehead Building is named, the story came to life. The adventures of a physician in territorial days, the flurry of life in a family with five children, the glimpses of Juneau as it was from 1935 to 1966—the William Whitehead story is a piece of Alaska history.

The Whitehead Building was the first building on the Auke Lake campus. It was completed in 1969 and housed offices, classrooms, and the library of what was then the Juneau-Douglas Community College. The University of Alaska Southeast was organized in 1972 and the building was dedicated to William Massie Whitehead and his wife Dorothy Johnson Whitehead.

William Whitehead was born in Virginia in 1905. Virginia Whitehead Breeze, Whitehead's

daughter and a former University of Alaska (UA) regent, has written about her father,

noting in an article that his high school classmates voted him biggest bonehead and

most athletic boy during their senior year.

After graduating from the University of Virginia (UV) Medical School in 1931, he moved

to Seattle to intern under a 1905 UV Medical School graduate, Dr. James Tate Mason.

The facility was the Virginia Mason Hospital, named for Dr. Mason's daughter.

After Whitehead's internship, he worked as a ship's physician for a time, traveling

to China, Japan, and the Philippines. In 1934 he moved to Wrangell, a community that

badly needed a doctor. "I had to eat," he told his family later of the move to Alaska.

"This country was in a depression and I couldn't make ends meet."

In Wrangell, he met Dorothy Johnson, the 24-year old daughter of Norwegian and Swedish

pioneers. She was an economics graduate of Whitman College in Washington State, where

she had been vice president of the student body and elected to Phi Beta Kappa. They

were married in September 1934, and moved to Juneau (population 7,500 at the time)

the following year.

They lived in a house at Sixth and Harris Streets that is now the Juneau Youth Hostel. It was located just across the street from St. Ann's Hospital, and Stuart Whitehead recalls that his dad would pull his pants on over his pajamas to run across the street and deliver babies at night. From his open bedroom window he could hear his dad yelling at the women in labor to "push, push!"

Whitehead's most satisfying work as a physician was delivering babies. "It's the happiest branch of medicine," he said, "I wouldn't be a brain surgeon for all the tea in China." He delivered an estimated 4,000 babies during his career. In 1934, after just arriving in Wrangell, he constructed an incubator out of a shoebox heated with a light bulb for a premature baby. "Hell, that kid grew up to be the town's best basketball player," he said later.

Daughter Virginia writes of her father that his warm, folksy manner put patients at ease. "He whistled as he walked down the hospital corridors for his was a jolly nature, and he liked to visit patients who weren't always his own during hospital rounds just to say hello and find out what was going on . . . He was naturally comfortable with people from all walks of life and backgrounds." She recalls sitting at the dinner table and listening to her father's end of a phone conversation with the husband of a patient: "Tell me, young man was she nauseous? . . . All right, then, did she vomit? . . . Goddammit, man, did she puke?"

Son Stuart recalls making house calls with his father, and said his father often flew out to small villages to see sick patients.

After a major 1939 fire in the Goldstein Building destroyed the offices of Whitehead

and his three partners, the Juneau Clinic relocated above the Alaska Laundry on South

Franklin. As one of its services, the clinic gave weekly checkups to local prostitutes

until prostitution was declared illegal in the 1950s. Whitehead's partnership continued

until a year before his death when he established a clinic under his own name on Willoughby

Avenue.

The Whiteheads were avid gardeners who cultivated a large flower and vegetable garden

at their cabin at Lena Beach. Dr. Whitehead loved to wear a pansy in his lapel during

the summer, and deliver homegrown flowers and vegetables to friends and neighbors.

In a January 1942 photo spread on Alaska's defense readiness, Life magazine featured Dr. Whitehead with the caption: "Warned of war, Dr. Whitehead of Juneau built the territory's first bomb shelter." The photo shows Whitehead shoveling snow in front of the air-raid shelter located behind their house. The concrete bunker is still visible behind the Youth Hostel.

Both Whiteheads were active in civic affairs, especially the Holy Trinity Episcopal

Church and the American Cancer Society. Whitehead served as president of Rotary and

the Chamber of Commerce, and was chair of the first Alaska State Judicial Council,

whose duty was to set up the court system immediately after statehood.

He then served in the House of Representatives (1963-65) while still a practicing

physician. Governor William A. Egan appointed him to the Board of Regents the year

before his death.

The Whiteheads died suddenly. Dr. Whitehead suffered a cerebral hemorrhage while on a hunting trip in November 1966, and Dorothy Whitehead was killed in a car accident in November 1971. They were each 61 years old when they died. They are buried in the Alaska Pioneers Plot in Evergreen Cemetery in Juneau.

Daughter Virginia wrote that only once did her father consider moving back to his home state. In 1942, he was offered an opportunity to take over a practice in Lynchburg, Virginia, and moved the family there. "But Alaska with its unique opportunities had reached the depths of his soul, and his Alaskan wife was homesick, so my father, with his young family in tow, returned in 1943 to the 'Great Land' far away from his roots."

Virginia speaks fondly about her memories of life in Juneau. "What was so remarkable

about my father's life was how well-rounded he was. Most doctors practice medicine

and hopefully spend time with their families. Our father did that—family was very

important to him and it was his idea more than my mother's to have a large family.

But he also enjoyed participating in public life, whether it was briefly, as it turned

out, as a member of the Board of Regents, or serving as chair of the first Judicial

Council and as a state legislator. Because we lived in Juneau, the capital, he kept

up his medical practice while he was in the legislature, delivering babies at night,

for instance, and skipping away from the capital to also do it during the day. He

also belonged to service clubs and professional medical organizations and worked hard

on the state Cancer Board as well as serving for years as a vestryman at the Episcopal

Church. He served on the territorial Board of Education for 14 years! And, on top

of that, he was an excellent businessman. No wonder he died at such a young age.

"And my mother was active, also, though she preferred to stay in the background. She

could put on a dinner for 50 people, however, and you'd never know she'd worked at

all. She just did it—made it simple. That's why I love the line on the plaque at UAS

that says about her, "and a helpmate always." She was, indeed."

Daughter Virginia says her father's warm, folksy manner put patients at ease. "He whistled as he walked down the hospital corridors for his was a jolly nature, and he liked to visit patients who weren't always his own during hospital rounds just to say hello and find out what was going on . . . He was naturally comfortable with people from all walks of life and backgrounds."

She recalls sitting at the dinner table and listening to her father's end of a phone conversation with the husband of a patient: "Tell me, young man was she nauseous? . . . All right, then, did she vomit? . . . Goddammit, man, did she puke?"

Son Stuart recalls making house calls with his father, and said his father often flew out to small villages to see sick patients.

After a major 1939 fire in the Goldstein Building destroyed the offices of Whitehead and his three partners, the Juneau Clinic relocated above the Alaska Laundry on South Franklin. As one of its services, the clinic gave weekly checkups to local prostitutes until prostitution was declared illegal in the 1950s. Whitehead's partnership continued until a year before his death when he established a clinic under his own name on Willoughby Avene.

The Whiteheads were avid gardeners who cultivated a large flower and vegetable garden at their cabin at Lena Beach. Dr. Whitehead loved to wear a pansy in his lapel during the summer, and deliver homegrown flowers and vegetables to friends and neighbors.

In a January 1942 photo spread on Alaska's defense readiness, Life magazine featured Dr. Whitehead with the caption: "Warned of war, Dr. Whitehead of Juneau built the territory's first bomb shelter." The photo shows Whitehead shoveling snow in front of the air-raid shelter located behind their house. The concrete bunker is still visible behind the Youth Hostel.

Both Whiteheads were active in civic affairs, especially the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church and the American Cancer Society. Whitehead served as president of Rotary and the Chamber of Commerce, and was chair of the first Alaska State Judicial Council, whose duty was to set up the court system immediately after statehood.

He then served in the House of Representatives (1963-65) while still a practicing physician. Governor William A. Egan appointed him to the Board of Regents the year before his death.

The Whiteheads died suddenly. Dr. Whitehead suffered a cerebral hemorrhange while on a hunting trip in November 1966, and Dorothy Whitehead was killed in a car accident in November 1971. They were each 61 years old when they died. They are buried in the Alaska Pioneers Plot in Evergreen Cemetery in Juneau.

Daughter Virginia wrote that only once did her father consider moving back to his home state. In 1942, he was offered an opportunity to take over a practice in Lynchburg, Virginia, and moved the family there. "But Alaska with its unique opportunities had reached the depths of his soul, and his Alaskan wife was homesick, so my father, with his young family in tow, returned in 1943 to the 'Great Land' far away from his roots."

Virginia speaks fondly about her memories of life in Juneau. "What was so remarkable about my father's life was how well-rounded he was. Most doctors practice medicine and hopefully spend time with their families. Our father did that—family was very important to him and it was his idea more than my mother's to have a large family. But he also enjoyed participating in public life, whether it was briefly, as it turned out, as a member of the Board of Regents, or serving as chair of the first Judicial Council and as a state legislator. Because we lived in Juneau, the capital, he kept up his medical practice while he was in the legislature, delivering babies at night, for instance, and skipping away from the Capitol to also do it during the day. He also belonged to service clubs and professional medical organizations and worked hard on the state Cancer Board as well as serving for years as a vestryman at the Episcopal Church. He served on the territorial Board of Education for 14 years! And, on top of that, he was an excellent businessman. No wonder he died at such a young age.

"And my mother was active, also, though she preferred to stay in the background. She could put on a dinner for 50 people, however, and you'd never know she'd worked at all. She just did it—made it simple. That's why I love the line on the plaque at UAS that says about her, 'and a helpmate always.' She was, indeed."

UA Site named William Whitehead:

STORY INFO:

A portrait of Dr. Whitehead hangs in the Whitehead Building.

The original article was printed in the Whalesong December 12, 1997 and was written by Eileen Wagner

Photos: Unless otherwise noted all photos are the courtesy of Virginia Whitehead Breeze.

The text has slightly been reworked as further information was gathered.

Editor's Note: Thanks to Virginia Whitehead Breeze, Stuart Whitehead, and Scott Foster for material contained in this article.

More than one doctor, Letter to the editor - February 3, 2003, Virginia Whitehead Breeze