Unique Kugeri Stands on Little Diomede Island - Part 1

A kugeri is a large Eskimo house, similar in nearly all respects to the common house or igloo. The differences are those of size and use.

An igloo floor space was generally 3 meters by 3 meters, while the kugeri was generally

greater than 4 by 4 meters. The igloo usually had a bench on the wall opposite the

entry hole; the kugeri always had benches around all four walls. In recent times both

types of house were individually owned and served as dwellings for one or more families.

The kugeri, however, because of its larger size and greater seating capacity, also

served an important social function as a central meeting place.

There were always more igloos than kugeris, and today the Little Diomede kugeri is

the last remaining house of this type.

Little Diomede Island is located at the narrowest place in the Bering Strait, between

the Chukchi Peninsula to the west and the Seward Peninsula to the east, where the

weather can be very severe.

This semi-subterranean house is an excellent structure for the arctic climate. It is intrinsically well insulated and low enough to be out of the cold, biting winds.

Most of the people of the Bering Strait lived in similar houses for at least part of the year; the Little Diomede people were unique in the area because they inhabited their homes year-round. They did not move to a separate summer dwelling, except when traveling to the mainland, where they camped under their skin-covered boats or umiaks.

The neighboring people of Wales and Port Clarence found it necessary to travel great distances to find the resources they needed to survive; the Diomede Islanders usually found much of what they needed in their home area. All the materials necessary for house construction were available on the island—stone, driftwood, whalebone, and sod.

The people of Wales and Port Clarence were culturally very similar to the Little Diomede people, but because the Diomede Islanders had an abundance of stone to work with and used it extensively, their homes had a unique design and appearance.

At Wales, semi-subterranean homes were built in the soft sand and loam along the coast

(Thornton, H.R. 1931. Among the Eskimos of Wales, Alaska 1880-1883. Johns Hopkins

Press, Baltimore); at Port Clarence the soil was not suitable for this type of construction,

so the houses were built partially above ground.

The first written description of a Little Diomede house came from Ivan Kobelev in

1779:

They lived in wooden dwellings covered with stone and sod. The entrance - exit

was made underground, about four sazhens (28 feet) long, but some had a hole cut in

the floor which also served as the entrance. In the ceiling there was a small window

covered with skin peeled from the whale's liver. Their wood was fir and cottonwood

that had drifted from America. They boiled oil for cooking in the winter. (Ray, D.J.

1975. The Eskimos of Bering Strait, 1650-1898. University of Washington Press, Seattle

and London.)

Lgnaluk, the Eskimo settlement on Little Diomede, is constructed on a talus slope

of weathered bedrock above the only landing area on the island suitable for umiaks.

As of December 1975, the population there was 104 full- and part-time residents. (Selkregg,

L.L. 1975. Alaska Regional Profiles, Northwest Region. Arctic Environmental Information

and Data Center, University of Alaska, Anchorage). Favorable construction sites are

limited, and most of the dwellings on the island are grouped together near the base

of the inclining slope.

Many of the newer structures are built on the remains of former habitations because

of the limited area for expansion.

The Little Diomede kugeri is built into the side of the rock-covered slope above the

landing beach. True to its type, it is a semi-subterranean structure built primarily

of stone, driftwood and whalebone, and now includes milled lumber. The entry faces

Big Diomede Island across the Bering Sea to the west.

The kugeri's living area is at the end of a tunnel. Tunnel walls are constructed of

piled sub-angular granite cobbles and boulders, braced at irregular intervals with

timber supports and plywood sections. The stones making up the ceiling of the tunnel

are held in place with whale ribs in the section of tunnel nearest the house and with

precut lumber pieces in the forward area.

The tunnel is wider and taller near the front entry than near the house entry hole,

making it necessary to stoop as one enters the house. The tunnel floor is covered

with large flat stones and slopes upward at 20 degrees from the entry to its back

wall.

Inside the entry is a storeroom for hunting equipment and various household items.

The door is hinged in three places with pieces of sealskin nailed in place. Formerly

a square tent covered with walrus hide was used as a storeroom.

Access to the single room of the house is through a circular entry hole in the floorboards,

which are pieced together around the entry hole and are removable to allow larger

items to be brought in.

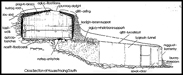

Larger Cross Section Image of kugeri. In the drawing the terms for the dwelling's parts are given, as much as possible, as the people of Ignaluk would give them. However the Little Diomede dialect is imperfectly known, so these translations are only the best transcriptions possible without a more extensive linguistic analysis. Reprinted from: Now in the North. Volume 12. Number 2. May 1982. University of Alaska Statewide.