Part 2

Part 2

This article appeared in the Jan. 1, 1983 issue of The Oregonian. Story by Tad Bartimus of the Associated Press

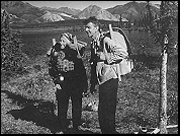

Mardy Murie's field biologist husband, so precise in his specimens, drawings, and reports to the Biological Survey (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), needed her hand at the helm of the household routine.

"I sort of worship efficiency," says the woman who often lived for weeks with three children in a 8-by-10-foot tent while her mate studied elk in the meadows of Jackson Hole.

Murie speaks with calm firmness. She seems to draw her manner from the natural world

surrounding her. She walks softly but with a sure foot, careful not to snap a twig

or disturb a wildflower. She abandons an alpine trail to give right-of-way to a moose

who takes priority in her order of things.

She punctuates a paragraph with a pause to watch a grouse glide by, then resumes talking

when the winged passage is done.

"I was destined for the outdoors. My stepfather always said there must have been some

gypsy in me. He'd say, 'Oh, that one—if she fell in the creek she'd come up with an

apron of fish.'"

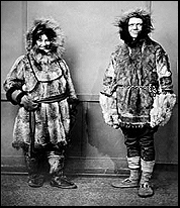

Born in Seattle in 1902, her wilderness odyssey began at the age of 9. She boarded a steamer with her mother and went north to Alaska to join her stepfather in the gold rush settlements of Fairbanks.

After three years of college "outside," as Alaskans call the lower 48 states, Mardy Gillette returned to Fairbanks for her senior year at the new Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines. In 1924 she became the first woman to be graduated from what is now the University of Alaska.

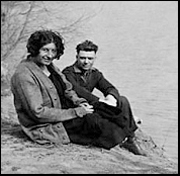

By then she had met Olaus, a Minnesota native born to Norwegian immigrants who were exploring the vast, uncharted interior of Alaska for the Biological Survey. Their three-year courtship culminated in a wedding Aug. 19, 1924, in a little Episcopal mission at Anvik, on the Yukon River. The newlyweds then steamed up the Yukon to the Koyukuk River to await the winter freeze-up that would enable them to travel the north country by dogsled while Olaus studied migrating caribou.

During their first month of marriage, she kept house in a loaned cabin and prepared

for the journey. She was only 20.

"I thought of all the women who have kept a log cabin warm and ready on the far reaches

of various frontiers," she wrote in her book, "Two in the Far North."

"As I worked I thought of these women, feeling kinship with them. Confusing, being

a woman, eagerness for the new adventure fighting within one with love of a cozy homekeeping.

Did men ever feel pulled this way?"

During the three-month trip, the couple had its first separation—Olaus left Mardy

at camp while he roamed far away. He didn't return on time. When he finally did get

back, his bride made a major decision—she resolved not to worry.

Later she wrote: "That hour on the snowy mountainside was good for me. I came to terms with being a scientist's wife. Since then, in many camps, in many mountains, I have waited, and fed the children, and put them into their sleeping bags, and still, long past the normal hour, have kept busy—and waited."

So that is how they spent their life together. She the helpmate, always flexible,

he the man whose family went everywhere.

In 1927, the Muries moved to Jackson Hole for good. In 1946, they bought 77 acres within the shadow of the Teton Mountains and moved into a log cabin where Mrs. Murie now lives. She sold her land to the National Park Service in 1966, but retains a 25-year lease which, she says, "ought to be enough to see me through."

Although her closest neighbors are the animals of the Grand Teton National Park, she

has many friends in the settlement of Moose and the nearby town of Jackson Hole.

Hardly a day passes that someone doesn't drop by to visit. Frequently it's at 4 p.m., the afternoon tea time she scrupulously observes. There is always a plentiful supply of "cry babies," her special ginger cookies with drippy white icing.

Sitting in her comfortable armchair, her white hair neatly braided in a bun, her jewelry

discreet and her clothes spotlessly pressed, Murie takes obvious delight in the enthusiasm

of guests who are decades younger than she.

"Most of my connections these days are young people," she says. As she speaks, her

strong profile appears in bas relief against the giant mountain of granite just beyond

her living room window.

"As many of my contemporaries grew older, they seemed to get narrower and narrower

in their views, and I couldn't talk to them anymore. I feel complimented that young

people seem to seek me out."

They flock to her. Foreign climbers, visiting dignitaries, environmental leaders,

fifth graders from science school.

The conversations always come around to nature, the environment, the future.

Some recent thoughts from Mardy Murie:

"One of the things that some people in the environmental movement need to learn is how to listen more and be less rigid. I say,'Come, let us reason together.' I'm so grateful that much of Alaska has been saved. It was a cleansing thing. Alaska is a nonending savings account that goes on forever."

"If we saved every bit of wild country left in the United States right now it wouldn't be enough for future generations, because of population increases."

"We must work harder to create some nature in cities. Urban parks are very important.

Sometimes that can be what saves people from despair. Suburbia is about the worst

of all of our American institutions."

In winter Murie cross-country skis every day. "When I'm on skis I try to forget everything

but what I'm seeing. I try to become a creature of nature."

Each morning she cooks a big breakfast on her faithful wood stove, then works on correspondence

and publishing projects.

She loves to go out with her young friends for Mexican food, walks at least a half-mile in the summertime, and between June and September takes a daily dip in the cold waters of her favorite swimming hole, a quiet pool in the Snake River.

Margaret Murie is also mentioned in this article:

Class of 2005 - following in the footsteps of John S. Shanly

Links:

Margaret Murie died in her home October 19, 2003. She was 101 years old. Margaret Murie's obituary

1998 Presidential Medal of Freedom awarded to Margaret Murie

1998 Robert Marshall Award Winner

2000 Wyoming Citizen on the Century

The Wilderness Society, an article about Mardy Murie.

Recipient of the State of Washington Governor's Writers' Day Award for Island Between

Received Doctorate of Humane Letters from the University of Alaska for her outstanding contribution to the life and literature of the Northland.

Books/Video:

Murie, Margaret. Two in the Far North. 1962. Reissued by Don Schackleford 1997. Alaska Northwest Books, AK. ISBN: 088240489X

Bryant, Jennifer & Castro, Antonio. Margaret Murie: A Wilderness Life. Twentyfirst Century Books, NY. 1993. ISBN: 0805022201

Arctic Dance - The Mardy Murie Story. Arctic Dance is a documentary film, narrated by Harrison Ford, and a non-fiction book by Bonnie Kreps, written Charles Craighead which celebrates the life and times of Margaret E. Murie, the mother of the American conservation movement.

UAF Scholarships: (Olaus Murie Caribou Fellowship) Dr. David Klein established this scholarship to recognize academically excellent graduate students at UAF whose thesis projects have their major focus on the biology, ecology or management of caribou.