Falklands Fish to Alaskan Algae

Thomas Farrugia

Profession: Alaska Harmful Algae Bloom (AHAB) Program Coordinator for the Alaska Ocean Observing System

Degrees:

- Bachelor of Science in Biology, McGill University

- Master of Science in Marine Biology, California State University-Long Beach

- Doctorate in Fisheries, UAF

Thomas Farrugia’s career has taken him all over the world, and all over the food web as well – from managing Patagonian toothfish (aka Chilean sea bass) in the Falklands, to studying sharks in Monterey, to his current job monitoring harmful algal blooms in Alaska. Here he talks with us about his career path and offers some advice on ways to succeed in STEM.

Please tell me about your job.

Currently I work for the Alaska Ocean Observing System (AOOS) as the coordinator of a network called the Alaska Harmful Algal Bloom Network. AOOS has eyes on lots of different issues and one of the issues that’s been worked on for a while, but is just starting to coalesce now, is harmful algal blooms (or HABs) - called colloquially red tides, although they’re often not red. It is a big bloom of plankton, which is actually very natural and a lot of times beneficial.

Phytoplankton is the basis of a practically all food webs in the ocean. So, it is usually a good thing but there are a few species of phytoplankton that if they bloom can create toxins, which are a defensive mechanism against their predators. With those really high concentrations these phytoplankton produce a lot of toxins which can be bad if you’re in and around the water. It can also get ingested by a lot of filter feeders like shellfish, which can then go up the food chain into fish and birds and marine mammals.

In Alaska, many of our communities are very tied to their food sources in the ocean like fish, shellfish, and marine mammals, so these harmful blooms can have an effect on human health as well. Just last year, a person passed away after consuming shellfish they had harvested in Unalaska/Dutch Harbor.

In Florida they have a lot of red tides right now, but their impact is mostly on tourism because people don’t want to go to the beach – the bloom’s toxins actually aerosolize, and then people can’t breathe well and it gets into their eyes. So, HABs have both direct and indirect impacts on human populations.

I am actually relatively new to phytoplankton and algae. So, I’ve had to learn a lot of those dynamics; understanding what affects algae species involves a lot of chemistry as well as biology because they’re very dependent on water temperature and salinity, and all these other processes, and nutrients can impact their growth, and then physics and sunlight as well. It’s been a bit of a learning curve, but it hasn’t been difficult to get up to speed quickly having a science background and specifically a marine biology background.

What role does AOOS play in dealing with the blooms?

With Alaska having the largest coastline of any state and one of the largest land masses, we leverage a lot of work that’s being done by agencies, non-profits, academic institutions, tribal organizations, and governments to package and provide really cool products.

We have a platform called the Ocean Data Explorer which gets all sorts of data and presents it all simultaneously and overlaid on top of each other. It produces products and tools for things like oil spill responses, or if there’s seismic activity, how that might shape the coastline, or all kinds of different things.

Part of my job is to get information from all these different people and organizations that I’ve been working with out there to let everybody know the risks - integrating science with public health and communications. At the same time, I am working with other researchers on figuring out if there is a way of predicting these blooms, and predicting how toxic shellfish can be.

How did you originally become interested in marine sciences and fisheries?

I think every kid goes through a shark phase and a dinosaur phase. I really like dinosaurs, but I stuck with sharks and they were my entry to being interested in marine biology. A lot of what I did early on in my career was working on sharks and I still have hobby projects working on shark stuff. That was the hook, sharks, and then I realized there’s a lot more than sharks in the oceans. Then, seeing the impacts of human activity on the oceans got me interested in that aspect of it and fisheries was a natural outcome of that.

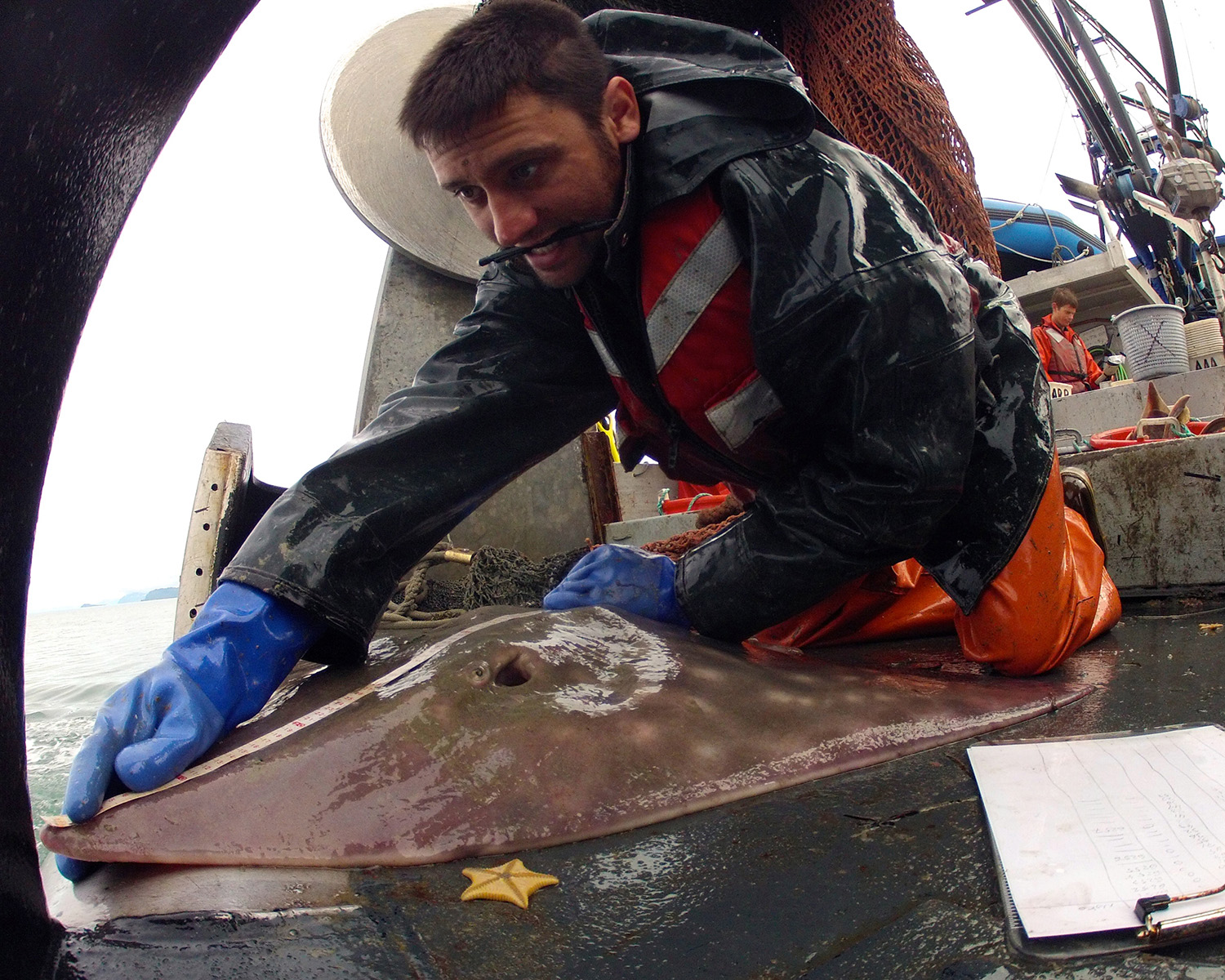

My first job out of undergraduate was working as a fisheries observer in Alaska. That really got me interested in how we collect data to understand the oceans. There’s so much stuff going on in the ocean, and there’s a whole army of people collecting ocean-based data from fish, fisheries, satellites and all these things.

As an observer I got to see a lot of this stuff, but I felt fairly limited in what I was able to contribute because you’re just collecting data - you’re eyes on the ocean, which is cool, but you’re then giving that data to somebody else to work on. So, I went and got my Master's in California in marine biology, and then I heard about a program up at UAF. So, I went straight from California up to Fairbanks to get my Ph.D. in fisheries.

UAF’s fisheries program is very well-known. There was a specific program at that time called IGERT (Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship). They trained graduate students in the interdisciplinary side of marine living resources. That was a really big part of how I learned how to translate science into other forms of communication, whether it’s policy, or outreach to the general public or to environmental groups.

While I was doing my Ph.D. in Alaska, I took a year off and went to D.C. and did a fellowship in the U.S. House of Representatives working on marine policy. It was great to do that as a part of furthering my education in a way that wasn’t just academic, but actually getting on-the-ground policy experience.

Tell me about your career path after your doctorate.

After I finished my Ph.D in 2017, the first job I got was in the Falkland Islands, in the South Atlantic just north of Antarctica. I was managing all of their Patagonian toothfish, which is also called Chilean sea bass - it’s a very popular fish in lots of restaurants, and really high-valued. I managed that whole multimillion-dollar fishery and that was extremely instructive and interesting.

I did that for about two and a half years, and then I got a job studying sharks at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. I started that in 2019 and it was supposed to be a longer-term career move, but once COVID hit, the aquarium had to close its doors for a long time and cut programs that weren’t aquarium-specific. I was on the research side so our whole program went away.

So, it has been an interesting two years: I went from the Falkland Islands to California back to Alaska. From fisheries, to white sharks, to algae all in a very short time span. I think that actually really speaks to the level of education that I got at UAF, as well as other places, to be able to transition and feel comfortable in all these subdisciplines. They’re all science, they’re all marine biology, but they’re quite different. Being able to adapt from one to the other, I don’t know that I would have been able to do that without the solid education that I got.

The fisheries program at UAF is really well-connected with industry and other groups throughout Alaska. A lot of the professors at UAF are also on committees and boards and you’re getting that additional perspective on a lot of situations outside of academia. One of my professors was on the statistical committee for the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council. He showed me how science was translated to policy through that committee, and I got a first-hand look which gave me a lot more than just an academic education. It gave me a more applied experience of getting that science into something that affects the real world in a tangible way.

How does your career differ from how you pictured it as a student?

When you’re going through undergrad and grad school, things are neatly compartmentalized for you. You go to this class and that class, and you study that topic really in-depth. But when you start working in these fields – at least in marine biology and fisheries – you realize that everything is on a continuum and there are no real categories.

You’ve got to learn a little bit about everything to really be able navigate what you want to do.

You can’t just focus on one or two things - at least, that was the case for me. When I was a student sometimes, I didn’t care about those other things. Take English, for example. I’ve never been good at it, I never cared too much about going to an English or literature class, but then you realize that you do so much writing as a scientist that you need to get good at that, you need to be comfortable writing. I think it’s not always clear that’s going to be a really important skill. You’re really focused on learning taxonomy, or processes and dynamics, and math and all that because you know those are going to be directly helpful. But as you start working in the real world you realize how important it is to be well-versed in lots of different disciplines. Even if you’re not doing it yourself, just being able to understand different vocabularies is extremely useful.

What other advice would you give to students considering a STEM career?

If you have a lot of different interests, chase the opportunities that are of interest to you that you come across. That really teaches you how to be adaptable and flexible which has been really helpful for me.

Don’t hesitate to talk to professors or to talk to people who are doing things that you find really cool, and see if there’s a way that you could get involved with what they’re doing. A lot of science is about networking and it is very hard to do things by yourself nowadays – you need to know so much to do stuff that the only real way to move forward is to do it collaboratively. So, talking to people, asking questions, making connections is extremely useful because you never know down the road who you are going to need to collaborate with or ask for guidance.

Interview by Courtney Breest, Alaska NSF EPSCoR. Click here for more Faces of STEM. All photos courtesy Thomas Farrugia except as otherwise noted.