With A Little Help From Her Friends

Mindy Kim Graham

Profession: Postdoctoral cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Department of Radiation Oncology & Molecular Radiation Sciences

Degrees:

- Bachelor’s in Chemistry, UAA

- PhD in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

- Postdoctoral Trainee in Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular Radiation Sciences, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Mindy Kim Graham works in one of the most important fields there is, cancer research. Along the way the UAA graduate has learned countless lessons about working in a team, gathering support and motivation from mentors and colleagues, and working through some of the vagaries of research in a huge and nuanced field.

Please tell me about your journey to your STEM career.

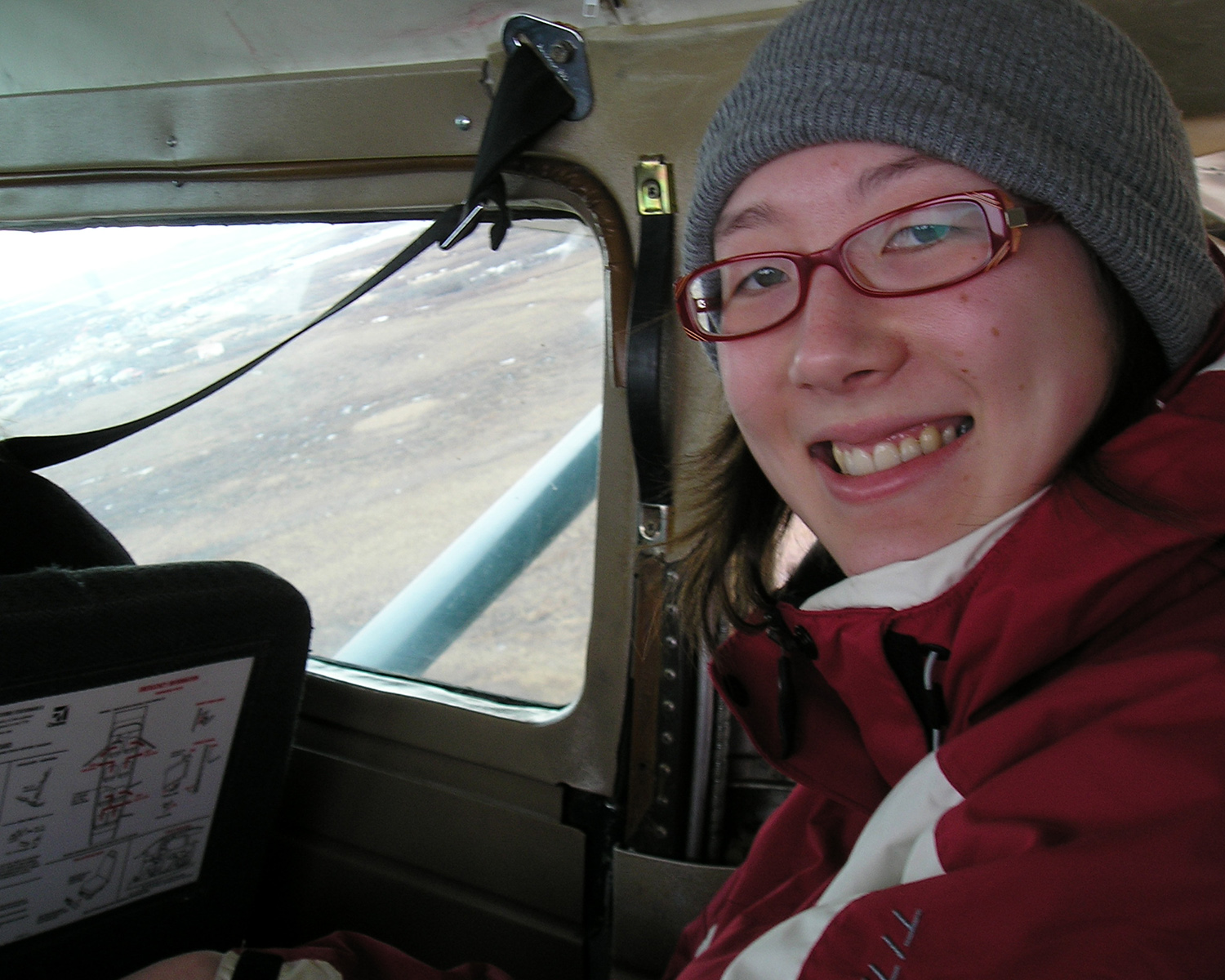

Most people don’t think about Palmer High when they think of a really good high school, but I had an excellent education. I got to explore things I thought were interesting, one of which was reading about wolf population dynamics with caribou. I did a project on that which got me interested in the field of biology overall, so when I picked my major at UAA I picked biology. I subsequently changed it to chemistry because I thought it would be more valuable to me.

When there was an excellent opportunity or what I felt like was an opportunity that I couldn’t pass up, that’s what really defined my trajectory. There are different schools of thought where some people feel like we should really specialize at an early age and we should know exactly what we want - but at that age you’ve had very limited life experience. How are you supposed to know?

When I started off as a biology major, I thought I should do something relevant to the field of biology and it would have made sense to do fieldwork in wildlife biology, but I saw a work-study opportunity at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). It’s right next to the UAA campus and you make a little money, so that’s nice when you’re a poor undergraduate. It was a really great place. I had a wonderful mentor who took a chance on me; it was my foray into bench (basic) research and I loved it.

That CDC work-study is where I became interested in the intersection of research and public health and how it can impact a community in a very positive way. I worked at the Arctic Investigations Program on a project exploring community-associated MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a type of bacteria that is resistant to several antibiotics) which was an issue in some communities in Alaska.

What was your next step after UAA?

That project got me interested in doing biology with an emphasis on human health, so I applied and was accepted to the School of Public Health at John Hopkins. They had the number one public health school in the nation and that is still true today.

When you’re a graduate student you spend your first year trying out different lab environments, different research projects, and see which one is the best fit. There was one lab – Dr. Paul Miller, who was a hardcore chemist, he did synthesis for these different types of modified nucleic acids. I thought the research was interesting, but I really picked that lab because I thought he was amazing and he was the type of mentor that I wanted. He was very soft-spoken and had an incredible wealth of knowledge. In that lab I got exposed to prostate cancer research, or cancer research in general.

Almost everyone knows someone who has died of cancer. We have been battling cancer for decades now and we have made progress on a lot of different cancers, but there are still a lot of people today who die from cancer. I have friends who have passed away from it, I have a friend whose mother passed away from it, and it is truly heartbreaking to see that. So, while I am interested in research and in biology, I really care about the prospect of maybe improving outcomes for a patient.

And it is a huge effort. There are so many people working on this problem, and there should be lots of people. There need to be many different types of perspectives, experiences, and expertise. The more we’re learning about it the more complicated and multifaceted we’re finding it to be. Even if you have the same cancer, depending on the mutations people have it could lead to different outcomes.

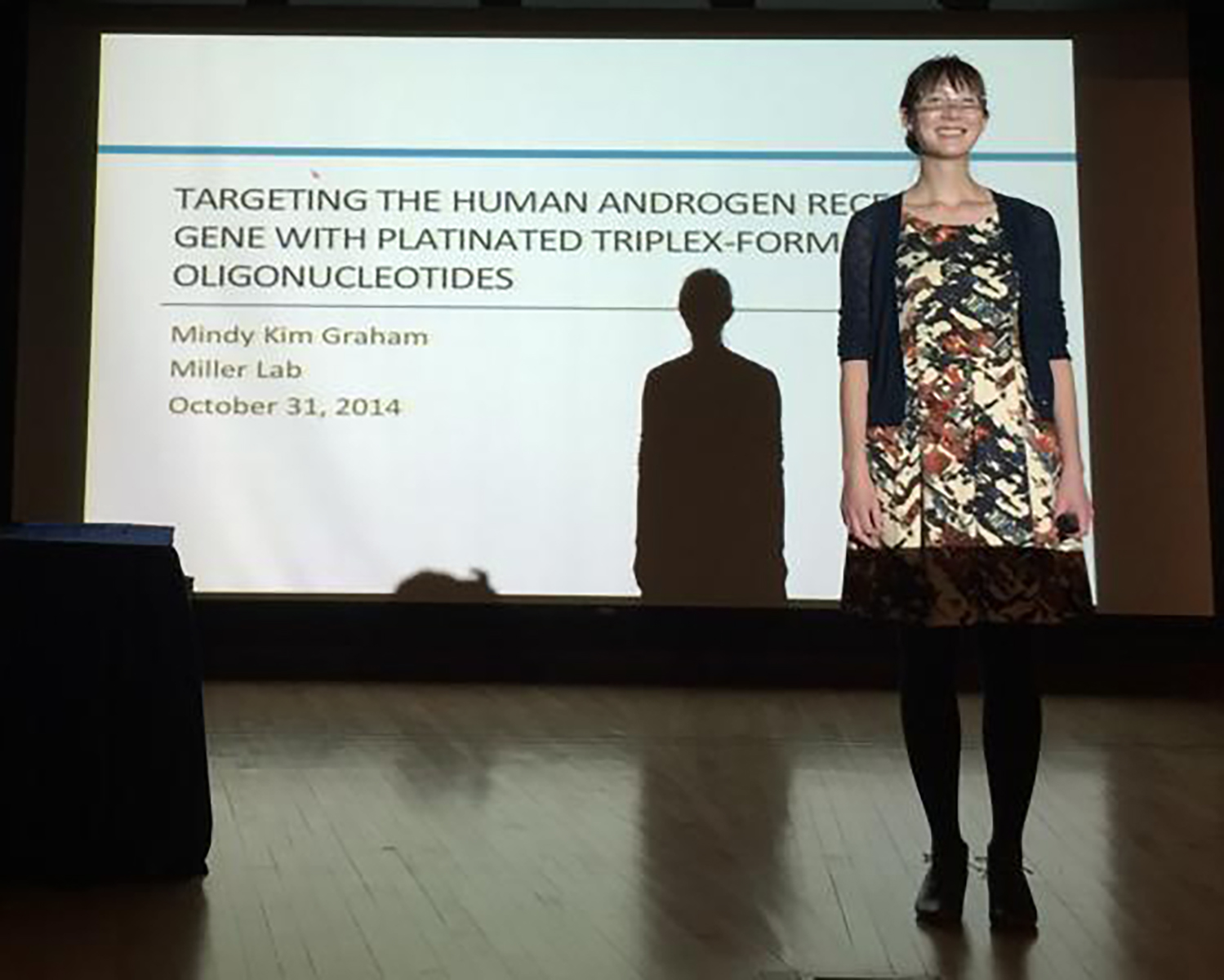

I did my Ph.D work targeting a gene called the androgen receptor gene that is important in prostate cancer establishment and progression. I used this special type of nucleic acid that has some unusual binding properties. I leveraged that as a way to draw in and target this important gene in prostate cancer.

Tell us about your activities after receiving your Ph.D.

After you’ve completed your Ph.D its very common in the biological field to do additional training, and this is called post-doctoral training. This is supposed to set you up for your future career trajectory, whether that’s in industry or in academia.

For my first post-doctoral fellowship I was interested in doing something more translational and relevant to cell biology. So, I studied telomeres (the ends of chromosomes) for about four years. Then I ended up doing a second postdoc, which is what I am doing right now. After my first post-doctoral fellowship, I didn’t feel like I had all the necessary skills that I wanted before trying to establish an independent career, I wanted more training. It is non-traditional to do a second postdoc and some people would frown on it, but I think for myself - if you’re going to spend the rest of your life doing a thing, you might as well feel pretty good about it.

What is the focus of your current postdoc?

What I’m doing now involves sequencing analysis. In particular, the type of specialized technique is called single-cell RNA sequencing, and what that means is for every single cell, you’re getting all of the RNA, which is the messenger RNA sequencing information. This is a relatively new type of technology and it is in incredibly high demand.

There are a lot of benefits to this technique; there is a wealth of information you can leverage in thinking about how to translate the bench science into something that will ultimately benefit a patient. I felt like I really needed that skillset. I am still doing training, but I am coming to the tail end of that and I will probably start applying for positions.

My goal is to try and stay in an academic institution. I think there is more opportunity in academia for discovery and creative freedom. When running your own lab you get to focus your energy on what you think are the most exciting aspects of your research.

What advice do you have for students?

I would encourage students to get real-life experience at the bench. There is nothing like real-life experience. Having some experience prior to making the decision of whether or not you’re going to go into medicine, or into a nursing program, or be an engineer or be a bench scientist or a computational biologist is so important.

If someone finds that benchwork isn’t for them, but they really like science, I would also recommend exploring other labs because a lab environment and community can be so different from lab to lab. Some labs are super huge, and people may never see their mentor, but other labs are small and people there may have a lot of time with their mentor and get a lot of input.

I think anyone who is successful in STEM, their mentors are such a huge part of it. I was fortunate, I was co-mentored. If you can be co-mentored that’s awesome because you’re getting two different perspectives. When I went to UAA for undergrad I was co-mentored by Dr. John Kennish over at the Department of Chemistry and Dr. Karen Rudolph over at the CDC and they were great. They let me visit their office to talk about making those important career decisions, but they were also cheerleaders. It’s so nice when someone believes in you because it gives you the motivation and the confidence to pursue something.

I remember when I was applying for Ph.D programs I was intimidated by the process, but I had a group of cheerleaders and I’m glad that I did. Otherwise I think it is very easy to limit yourself and to underestimate your own abilities.

Were there challenges you faced that other students could learn from?

There were many times that I felt like I might not be on the right path, and that’s an ongoing experience. No matter how good other people think I’m doing, I never feel like I’m doing enough, or am good enough. Other people have touched on this, impostor syndrome, this feeling like I don’t belong here. It is still ongoing, but my attitude is, well, I’ll keep going as long as there are people who believe in me, the people whose opinions I care about. For example, I care about my mentors’ opinion about what they think of me because they know me better.

In spite of the criticism, despite what you think other people may think of you, you have to just keep trying until you can’t anymore. That’s been my attitude, I’ll keep trying even if I don’t think I’m good enough, even if I think other people don’t think I’m good enough. If it doesn’t work out it doesn’t work out, but my self-doubt shouldn’t be a reason that stops me from trying. You learn by failure, that’s how you get better.

What is different in your career than you expected as a student?

One thing I’m finding about biology is that you do a lot of work and the product that comes out of it is small. For example, you’ll spend years and years at the bench doing an experiment and you get the results, and you publish findings that are relevant and important to the field that move the field forward. For that one paper where there might be five figures, but you’ve generated hundreds of different figures. There are a lot of diverging paths when you’re doing experiments and the goal is to let your data tell you what it is saying, to track that down, and follow it up with a narrative.

Also, as a biology student, as long as you study hard and work hard you will get a grade that usually reflects your effort. In biology research that’s not always true. If you’re working in a relatively unknown field where there isn’t a lot of research, you can expend a lot of effort trying to figure something out and you might not be able to do it because the resources aren’t there, the technology hasn’t caught up yet, or the information you need to discover a pathway hasn’t been discovered yet.

You have to try and not take it personally if things don’t work out the way you want them to. Sometimes you’ll have a hypothesis and your data is telling you that you are not correct, and that’s okay. I think oftentimes people get upset about it. I think it’s important for anybody in research to not get bogged down if you’re putting a lot of effort in and don’t feel like you’re getting the gratification of that effort, in the sense of publications or worthy data.

There are so many times when I’m working on something and I’ll feel inadequate and I’ll feel like I should know more but that’s okay, that’s part of research and a part of discovering something new. If you enjoy the process and you can put ego aside then it can be a very worthwhile adventure, an exploration and investigation.

Interview by Courtney Breest, Alaska NSF EPSCoR. Click here for more Faces of STEM. All photos courtesy Mindy Kim Graham.