Hunting for Data

A Fire & Ice undergraduate reached back almost a century to help validate some modern climate modeling software.

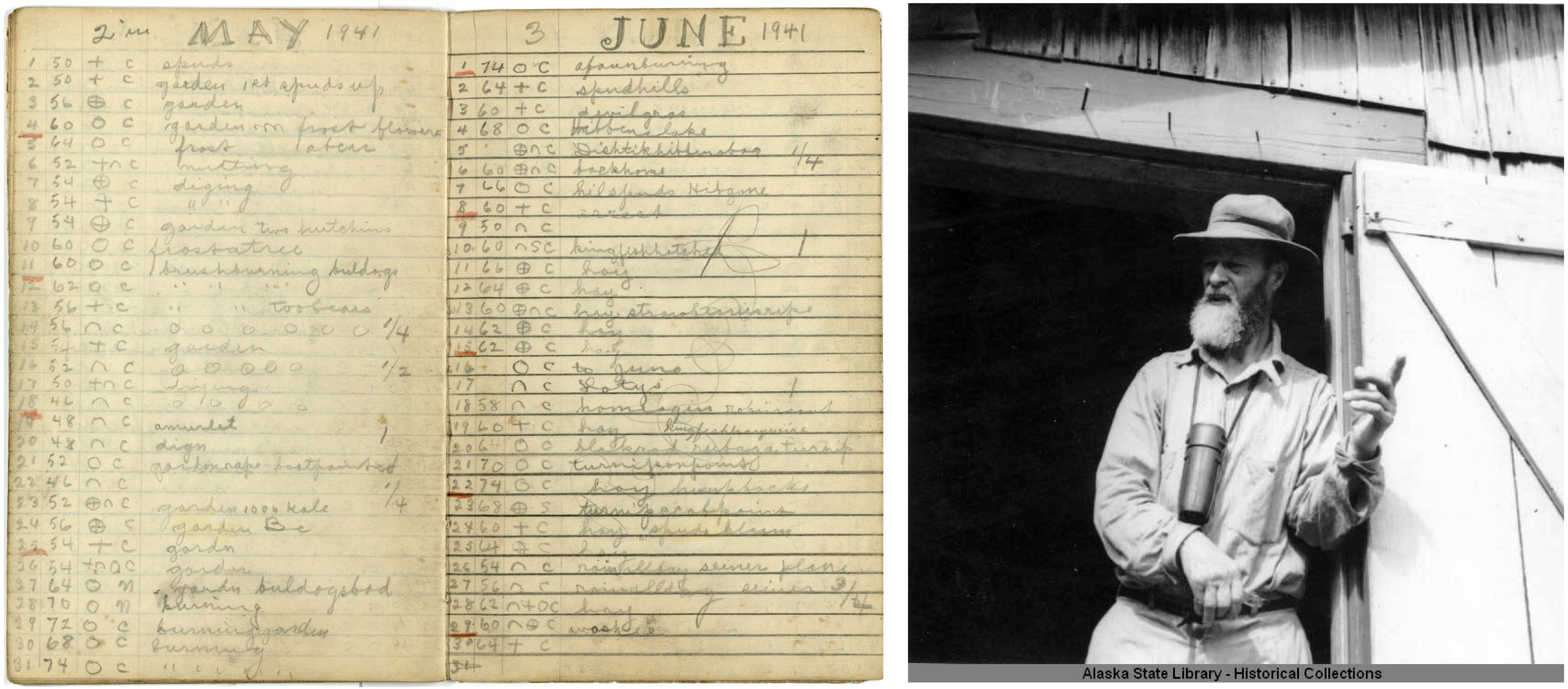

UAF Ocean Sciences major Emily Williamson is lead author on a recent paper published in the PeerJ journal entitled “Independent validation of downscaled climate estimates from a coastal Alaska watershed using local historical weather journals.” Williamson and her co-author, UAF PhD candidate Chris Sergeant, tested the accuracy of ClimateNA climate-modeling software by comparing its results to temperature and precipitation data recorded from 1926-1954 by Allen Hasselborg, a homesteader on Admiralty Island outside of Juneau.

“If you’re using the ClimateNA model for a project in a really remote area, you really have no way of knowing how accurate the model is because there are not a lot of opportunities to test it against long-term, consistent weather data,” explained Williamson. “It was a rare opportunity to do that, because the area is so remote and it’s historical data from a pretty long time ago.”

Sergeant came up with the idea for the article after taking a packrafting and hiking trip across Admiralty Island that passed near the Mole Harbor homestead of Hasselborg, a renowned bear hunter who had also collected many specimens of Alaskan fauna for scientists. When Sergeant learned that Hasselborg had kept meticulous daily journals of precipitation and temperature, Sergeant hatched the idea of using the data to model historic streamflow – and recruited Williamson to help.

“I was a fisheries student at the time, and it seemed like it would be a good experience to learn about models,” Williamson said. “And I’m also really interested in natural history, so it seemed like a cool opportunity.”

Williamson received a Fire & Ice travel award to travel to Juneau in 2019, where she scanned the journals in page by page from their home at the Alaska State Library, then transcribed them all. “There were around 279 usable months of data, so it was a really long time period, 1926 to the ‘50s, and the author was pretty consistent,” she said. “It took quite a long time to transcribe it all.”

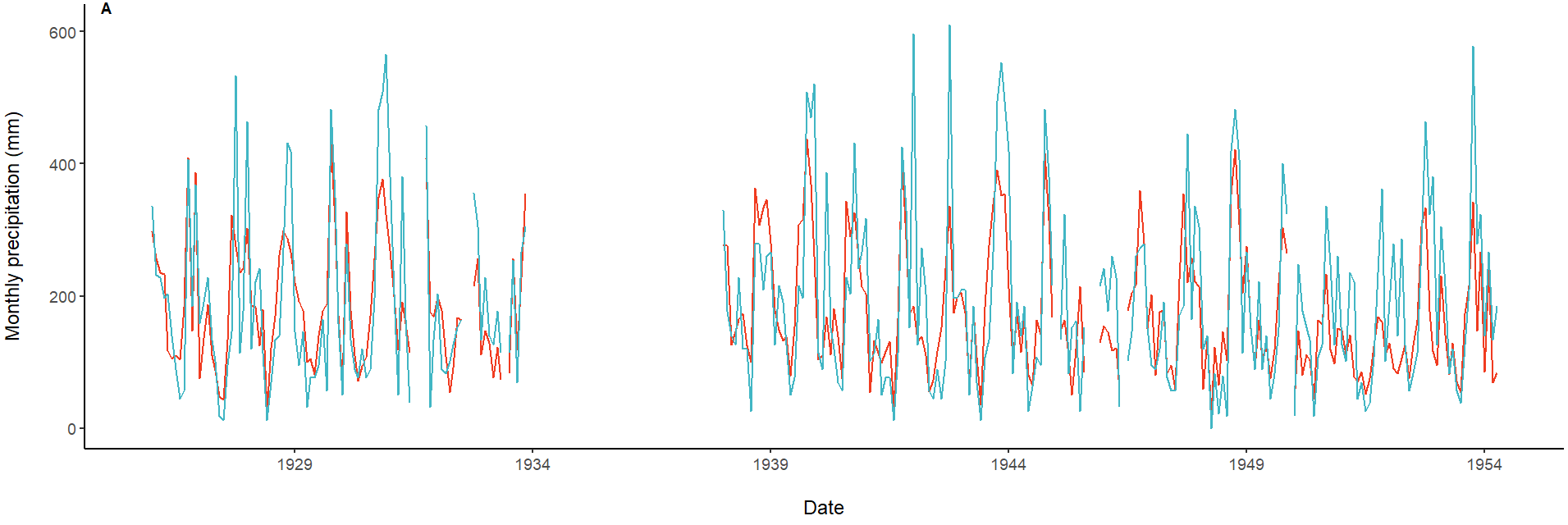

She and Sergeant ultimately decided it would be more fruitful to do a direct comparison of the temperature and precipitation data than to generate a streamflow model (though they did that as well). The pair used ClimateNA to model temperature and precipitation for the period of the journals and location of the homestead and compared the findings. They found a high correlation between modeled and observed measurements of monthly precipitation (0.74) and monthly mean of the maximum daily air temperature (ρ = 0.98). The modeled streamflow showed more moderate correlation (0.55).

Williamson said the correlations tended to be smaller in years of anomalously high or low temperature or precipitation, but the results largely validated

ClimateNA. “In general the trends are the same, they increase at the same time, they decrease at the same time,” she said. “And a lot of times the numbers are really similar.”

ClimateNA is a climate downscaling model, which means it uses data from weather stations – in this case, stations in places like Juneau and Sitka, far from Hasselborg’s homestead – and combines them with circulation patterns to estimate climate data for specific points on the map. By helping validate ClimateNA’s estimates, Williamson said the results could aid researchers studying remote sites.

“It’s showing that you can use downscaled climate data to make relatively accurate historical time series for anywhere in Alaska, no matter how remote it is,” she said “Even if your study site isn’t near a weather station, you can still have historical data for a study site if you want to do a project there, and you can compare that to current data and you can draw some conclusions about climate change.”

In addition to the Juneau travel award, Williamson has also been involved with the Fire & Ice project as a researcher. In summer 2019 she conducted fieldwork in Kachemak Bay for her advisor, Fire & Ice Principal Investigator Brenda Konar, and in summer 2020 she processed phytoplankton samples for F&I faculty hire Gwenn Hennon, an effort that formed the basis for her senior thesis. She plans to graduate in spring 2022.