Part 2

Part 2

By LarVern Keys

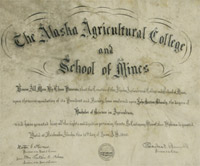

Believe it or not —we had a graduate at the close of our first year. John ("Jack") Shanly. He was graduated in agriculture.

We had a large room with a stage on the upper floor. It was used for mechanical drawing

and assemblies. For the graduation, we had to send Outside for the caps and gowns.

All well and good, but it proved to be a very hot day—all windows were open and mosquitoes

-- well, 'nuff said.

The members of the staff were seated on the platform at one end of the room. It was

hot, and the caps and gowns didn't help. There were oodles of mosquitoes. Need I say

more! There was a door at the back of the stage, and suddenly, through that door came

lighted smudge pots. The janitor shoved them near our individual chairs and the smoke

curled ceilingward. It was anything but dignified, but far more comfortable.

And so our first graduate received his diploma. The diploma was handmade and the printing

beautifully done by hand by a resident of Fairbanks.

And so closed that first year of the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines.

The Women's Room was always a sore spot with me. I would have liked a pleasant, restful

room. The president thought the "essentials" was all that was necessary; that the

"girls" and "boys" should spend any extra time in the library, studying.

So I managed a cot with a mattress and cover, one straight chair (not even a student

chair), and that was all. Even in 1935, when I left Alaska, that women's room still

just had the cot and (I believe) two straight chairs. I sincerely hope it is a nicer

room now. I have not seen it on my several trips north. I remember "borrowing" the

one and only chair in order to sit down beside a very sick student stretched out on

the cot.

The president put in long hours, regularly 8 to 5 and then usually 7 to 10 in the

evening. In the evening, he usually made notes for me to carry out the next day.

This having a secretary living in Fairbanks was not to his liking. Until the trolley

service got running better, it was hard for me to be back at work by 8 sharp and work

until at least 5. I worked "overtime" many times on Saturday and Sunday and, since

the jitney service on the railroad wasn't adjusted to the college schedule, it often

meant the three-mile walk along the railroad. I didn't mind the walk so much, except

I had to get out to the college by 8:00 a.m.!

The prex. finally came up with a solution. In the summer of '23, he blossomed out

in work clothes, laid out on paper what would be a possible street for faculty homes,

and selected a "lot" for the first "cabin." With some help from a student, he dug

the basement and then hired a carpenter to construct a three-room cabin—9x12 living

room, a bedroom just large enough for a double bed, small dresser, and tiny clothes

space, no water, no conveniences but a woodshed on behind. One hot day while he was

digging away, I received a call that an Austrian count was on the way out from Fairbanks

to see him. I hurried out to tell him. And the instructions given me—"Tell him I am

digging a basement! I would be pleased to have him come out here!!" So I tried to

be courteous and told the count where we would find the president. The count gasped,

"The president of a college digging a basement! You would never hear of such a thing

in my country." I tried to cover by telling the Count that the president just wanted

to get some exercise. When we arrived at the excavation, the president wiped his brow,

his hands, and proceeded to engage in a conversation as though there wasn't anything

unusual about the situation.

That cabin, when finished, was to be my quarters. It was the first living quarters

for faculty and staff—besides the President's home—on the campus. It turned out to

look quite respectable. I furnished it mostly from Sears Roebuck and paid the owner—the

president —$25 a month rent. I carried water from the College. I bought wood from

the students and electricity from the College. The real reason for the cottage was

to have me living on the campus so I would be closer to my "job" and more available.

I enjoyed my little house, and, in time, several others built or moved into houses

built by Jack Shanly at the foot of the hill.

Dress was no problem in those days. In fact, general attire for men students was usually

overalls, corduroy, or khaki pants, suspenders, any kind of shirt—no coat, informal

garb to say the least, suspenders in evidence everywhere.

The president decided we should have a museum. On the top floor, at the head of the

stairs, was quite a space. We bought a flat glass-topped cake display cabinet from

the bakery in Fairbanks and some of the boys wrestled it up the stairs. The President

placed a few artifacts from his private collection in the cabinet, and so the museum

was born.

The cabinet was not locked, and strange things had a way of appearing therein.

We had two brothers, Frosh from Quebec, John and Robert McCombe, and they were always

up to something. We had one senior —Jack Shanly. He had had three years at Cornell

and came to the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines for his fourth year.

One day, I discovered his suspenders in the "museum." The McCombes had swiped his

suspenders and placed them in the "museum." There was always something "different"

happening.

Shanly homesteaded an area at the foot of College Hill. He built two houses—California

style. Toward spring, he decided to invite the faculty down for dinner. He asked Elizabeth

Kirkpatrick and me to come down and help him. When we arrived, we found he hadn't

even started the dinner! Elizabeth went back up the hill and got the necessary utensils.

We worked like beavers and finally had some kind of a dinner ready—an hour late. Shanly

was no help at all. The principal thing I remember was he wanted to string decorative

lanterns out to the road. We got him to peeling potatoes. We were about ready and

he disappeared. Suddenly, he called from the bedroom, "Bring me my pants. They are

in the bedding on the cot." (The cot was to be part of the seating arrangement for

the guests). I found the "pants" in the bedding nicely laid out to retain the crease.

I handed the trousers in and pretty soon, he blossomed out, looking like a million

dollars. As for Elizabeth and I, we would have liked a leisurely hot bath and nap.

I don't remember just how the faculty guests got back to Fairbanks that night. None

of them had cars. I think some of them piled into a car in which they had come out

from Fairbanks. Elizabeth stayed with me. We never helped on another "Shanly" dinner!

One day, George Keys burst into the office. There was a "weakness" in the entrance

stairway. He had been investigating and found a box stored underneath. It was a case

of dynamite which was badly decomposed -- the nitroglycerin had melted and run out

into the box. Hard to tell how long the box had been there -- at least ten or twelve

years. Think what might have happened if it had been found by someone who was smoking.

George offered to dispose of it. He carried it out of the building and away from everything.

He put a lot of paper under the box, then attached the paper to a long pole, lighted

it, extended it to the box, and then ran! The box exploded and burned vigorously.

The prex. had a habit of taking off for Washington D.C. during the winter. He usually

went in November and would be gone perhaps five or six weeks. During his absence,

everything went through my office; even in later years when a dean had been appointed.

How I dreaded to have him go! Seems like something was always happening.

This article is just a "this and that" of things and experiences in those very first

years.

Just why, I am not too sure, but the president had a rigid rule that there would be

no pets on campus—and so that is the way it was. After I moved into my little house

on the "campus," I would have given a lot to have a kitten, but --. Along in the early

1930s, my husband and I did have a squirrel for a little while. He had the run of

the apartment, and it was fun. He had a wheel in the kitchen, but one day someone

left the outside door ajar and out he went! He "moved" into the college store house.

It was a small building behind the college kitchen and contained supplies much to

his delight. He amused himself stacking supplies along the walls until the caretaker

was successful in catching him and taking him back to the woods.

One winter, a cat was found in a vent pipe to the power plant. He had crawled into

the pipe to get warm. So he was kept in the power plant until it warmed sufficiently

to put him outdoors and let him rustle his own food. Another time. we found a woodpecker

curled up in a vent pipe. So screens were installed over the vent pipes!

I was always fussing about there being no trees or shrubs. It was so barren on that

hill top. Just why the president was opposed to even a few trees and shrubs, I will

never know. George Keys and I were married on January 3, 1925. The new power plant had been built with a nice apartment on the second floor, so that was our "home"

until we left in July of 1935. There was a bathroom! The only bathtub on the campus

except the one in the president's residence.

Early in 1926, we asked permission to plant three trees in a cluster at once side

of the power plant. Permission granted! We planted three native birch trees and they

remained there at least until 1977, I believe. Anyway, the space was needed for buildings.

George Keys and I were married on January 3, 1925, and I doubt if there has ever been

a wedding quite like it. I arrived in Seward from Seattle at 10 A.M. January 3rd.

I had come north on the steamship Alaska. At 8 p.m., George arrived in Seward from

the College. It was thirty-five degrees below zero. I met him at the train. We contacted

the justice of the peace and he agreed to marry us at 10 P.M., but said we would have

to have two witnesses. We didn't know anyone in Seward, so George went out (not many

on the street at that time of night and in that kind of weather) and brought in two

strange men. We were married at 10 P.M. by the justice of the peace with two strangers

as witnesses and in a large room with large windows fronting out on the street and

the whole place ablaze with lights. Anyway, we were declared properly married and

have the certificate. We celebrated our 59th wedding anniversary on January 3rd, 1984.

On the morning of January 4th, we left for the College and arrived there two days

later. We were met at College Station by a group of students banging on dish pans

and what have you. They carried our bags to our temporary quarters in the college

building. The next morning, the student body came down and chivaried us. Some cut

a beginners' law class taught by the president! He was so angry, he locked the classroom

door and gave them all zero for cutting class.

It was just one of his quirks. If any one of the staff married, he grumbled. George

offered him a cigar. He refused it. George said, "Come on, the one you have is so

short it will burn your fingers." The Prex grumbled and took the cigar.

The Prex, like all the rest of us, had his quirks, but he was a fine, honest, sincere,

noble, friendly man. I was in the office some seven years and in contact with him

from 1922-1935. In those first years, I learned a considerable amount about the political

side of the picture. The funny part was, he was a ardent Democrat and I was just as

ardent a Republican!

I am very glad he was chosen to be the new college's first President. It became his

life. It was not unusual for him to begin working at 7 a.m.. and, with his shirt sleeves

rolled up, cigar smoke curling up from an ashtray, he would work until midnight. Very

often at 8 a.m., I would find a stack of written material—letters to be transcribed,

bills to be paid, and instructions to be followed.

I was very much for upgrading the scholarship. The president, although an excellent

scholar at Bucknell, was very much for numbers. I was long on increasing scholarship.

We used to have great discussions on these subjects, especially between 1930 and 1935.

In 1931, hoping to help build up the scholarship side, George and I gave a bronze

plaque on which was to be inscribed the name of the freshman girl student who had

accomplished certain specifications.

My hope was that perhaps it would help girls to come forward more and accomplish more.

I guess I was sot of a suffragette without knowing it. Anyway, that is the history

of the first plaque. The Board—or somebody—reduced the scholastic requirements in

later years. I did not fully approve, but anyway, an award was made each year, and

the plaque award spaces were filled, I think, around 1955. We used to keep a fossil

ivory brooch in the safe in the President's office to be given to an award winner

as a small prize remembrance. After the plaque was filled with names, I decided to

"call it a day" and allow someone else to carry on in whatever way they felt best.

You see, I felt that to lower the average so someone could win each year, had lowered

the honor or achievement, and so had lost some of its purpose—namely, higher scholarship.

Perhaps I was too idealistic. I was the second in my class at my own graduation from

the University of Idaho in 1921 and I am still proud of that (forgive me).

A classmate and I, in our senior year, went to the president of the university and

asked about Phi Beta Kappa. Why didn't the U. of I. have it? That started the ball

rolling, and a few years later, there was a chapter there. I still was not a Phi Beta

Kappa. According to some rule, they did not take in former graduates. Then, in 1930,

by special decree, I was finally made a Phi Beta Kappa!

President Bunnell also received his Phi Beta Kappa key shortly after I did and then

he received his doctorate, which he should have had a long time before that time.

Back in '22, one of the first things I asked was, "What am I to call you? You are

no longer an active Judge and Mr. is not definitive enough." -- So I decided on "president"

-- and that is the origin of "president." In 1930, at long last, we could correctly

address him as Dr. Bunnell!

I am glad I had the opportunity to be at the College during its formative years. It

was hard work, but it was fun, exciting, fulfilling, and wonderful to be a part of

seeing and helping in its development.

I believed then -- and I believe now -- some 60 odd years later that the present University

of Alaska owes a very great deal of its present status of accomplishment to the foresight,

statesmanship, energy, ability, and constant upgrading management of its first president—Dr.

Charles E. Bunnell.