Alaska Innovators Hall of Fame inducts August G. (Augie) Hiebert, “Father of Alaska television”

From bringing television to the Last Frontier and building the first radio station in Fairbanks, to laying the groundwork for using satellite communication in Alaska, August G. (Augie) Hiebert’s vision laid the foundation for the evolution of mass communication in Alaska. The Alaska State Committee on Research honors Hiebert’s legendary accomplishments in the broadcast and communication industry, and inducts him into the Alaska Innovators Hall of Fame class of 2020.

“My Dad always had the foresight to see Alaska’s potential,” said Terry Puhr, Hiebert’s youngest daughter. “For him, the bottom line was never about money. He cared about what the community wanted and needed. He understood that geography isolated Alaskans from the Lower 48 and its impact on peoples’ wellbeing, so he made it his life’s work to connect our communities to the rest of the world with TV and radio.”

Hiebert's greatest and most lasting contribution to Alaska was his vision to use telecommunication and satellite communication technology to connect Alaskans throughout the state and to the outside world

. The “Father of Alaska television,” he leveraged a $25,000 inheritance from his friend, Cap Lathrop to establish KTVA, the state's first television station. KTVF in Fairbanks followed two years later.

Hiebert led negotiations with U.S. Military and Alaska’s congressional delegation to bring satellite feed of Neil Armstrong's walk on the moon July 20, 1969 to Alaskan television viewers. At that time, live events were usually pre-taped and shipped to Alaska, where events were broadcast weeks later. As a public service, Hiebert shared the live coverage of the moon walk with his competitors so that it aired on all three Anchorage television stations.

Born in Central Washington in 1916, Hiebert seemed to be born with an innate talent for radio and a flair for logical and creative innovation. At 15, he qualified for his first ham radio license and earned his own call letters, W7CBF. Hiebert soon began building his own radio equipment in his “ham shack” behind his family’s farmhouse to send and receive Morse Code.

Hiebert and a friend hooked up tone generators on a telephone party line so they could communicate through Morse Code. They quickly honed their skills and improved their speed. It wasn’t long before their party line neighbors complained about hearing their transmissions and banned them from the party line. That was when Hiebert moved the tone generators to a convenient barbed wire fence so he and his friend could continue their Morse Code transmissions.

In 1939, 22-year-old Hiebert was asked to come to Alaska to help build KFAR, the first radio station in Fairbanks. After establishing the 1,000-watt radio station, the next step was finding news content for their broadcasts. That was before the invention of satellite news feeds and the station didn’t have a teletype machine. Hiebert’s creative solution was to construct two large (850-feet in length) high frequency radio antennas pointed at New York and San Francisco.

He devoted hours each day listening to the blazingly fast Morse code signals received on these antennas, "code copying" at 40-50 words per minute so that he could share worldwide and national news stories with his listeners.

Hiebert recreated play-by-play baseball games from telegraph messages received by the military's communication system in Alaska. He used home-grown sound events to simulate the batting of the ball and the sound of the ball being caught in the catcher's glove. He was also the first person in Alaska to hear short wave radio messages of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, which ushered the United States into World War II. He shared that information with the commander of Ladd Air Force Base who notified the Alaska Defense Command.

Known for his passionate advocacy for advancing telecommunications in Alaska, Hiebert believed that satellite communication could be a cost-effective and reliable way to connect the state’s urban centers and remote communities with the rest of the world. Despite obstacles, he championed his belief through discussions with COMSAT and with government entities. His dream was realized when COMSAT constructed a satellite earth station near Talkeetna. This made it possible for the first live broadcast to Alaska— Armstrong’s small step and a giant leap for mankind.

That one satellite earth station led to a joint venture between the State of Alaska and RCA Alascom to construct more than 100 small 4.5-meter diameter antenna satellite earth stations in the smaller communities, and numerous 10-meter diameter earth stations in larger communities. This created a network that linked rural communities with affordable and much more reliable communication. In time, low-power TV transmitters were installed in most of the villages to receive an Anchorage-originated video feed of a mix of network programming. Thanks to Hiebert, the days of waiting for the video tape to arrive via jet for the 4-hour tape delayed news from Seattle were over.

“My Dad had a big heart,” said Puhr. “He would take Alaskan seafood to Washington, D.C. for ‘Taste of Alaska’ parties as a way to thank those at the FCC and the Alaska Congressional Delegation who helped facilitate the satellite telecommunication needs of our state. A month after 9-11 he brought seafood to a fire station in New York City on behalf of Alaska to thank the firefighters for their service. He lived his life in a spirit of gratitude.”

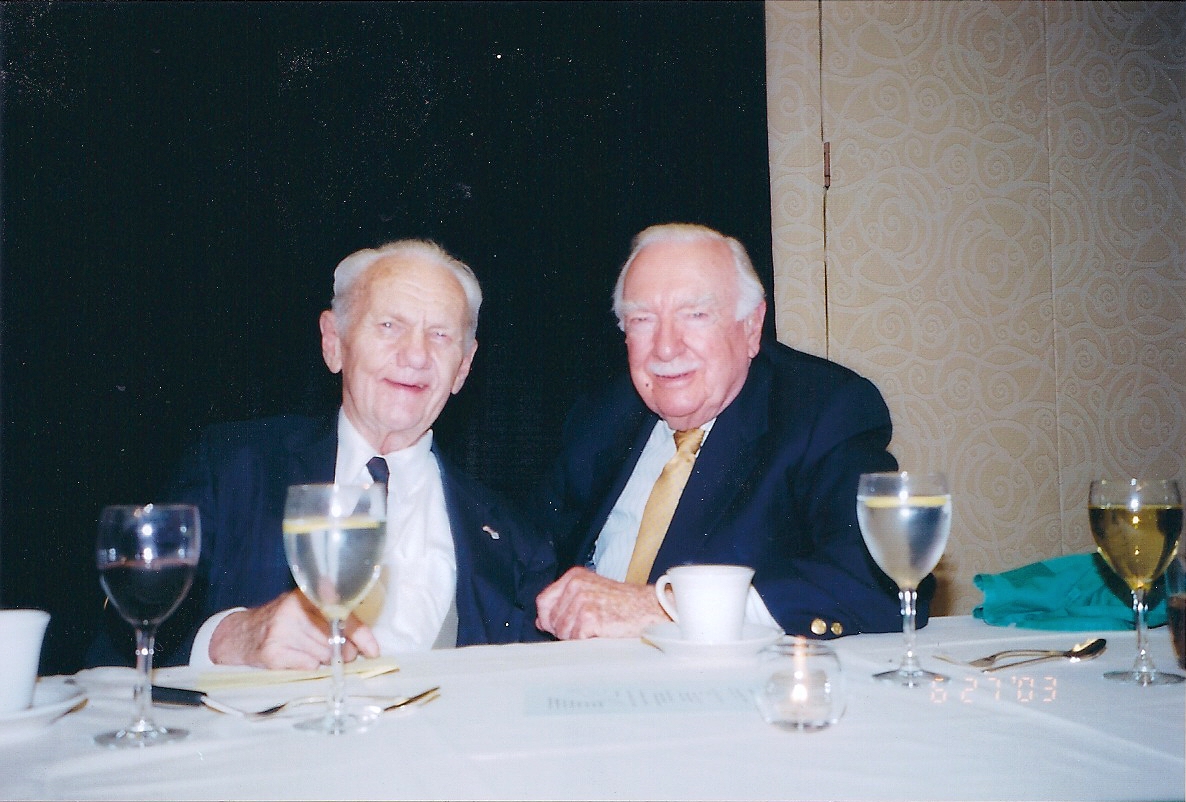

Hiebert passed away from cancer at age 90 in Anchorage. After Hiebert’s death, his friend Walter Cronkite said, “The great state of Alaska has lost one of its most distinguished citizens. Augie Hiebert was the pioneer of communications who brought radio and later television to his beloved home state.”