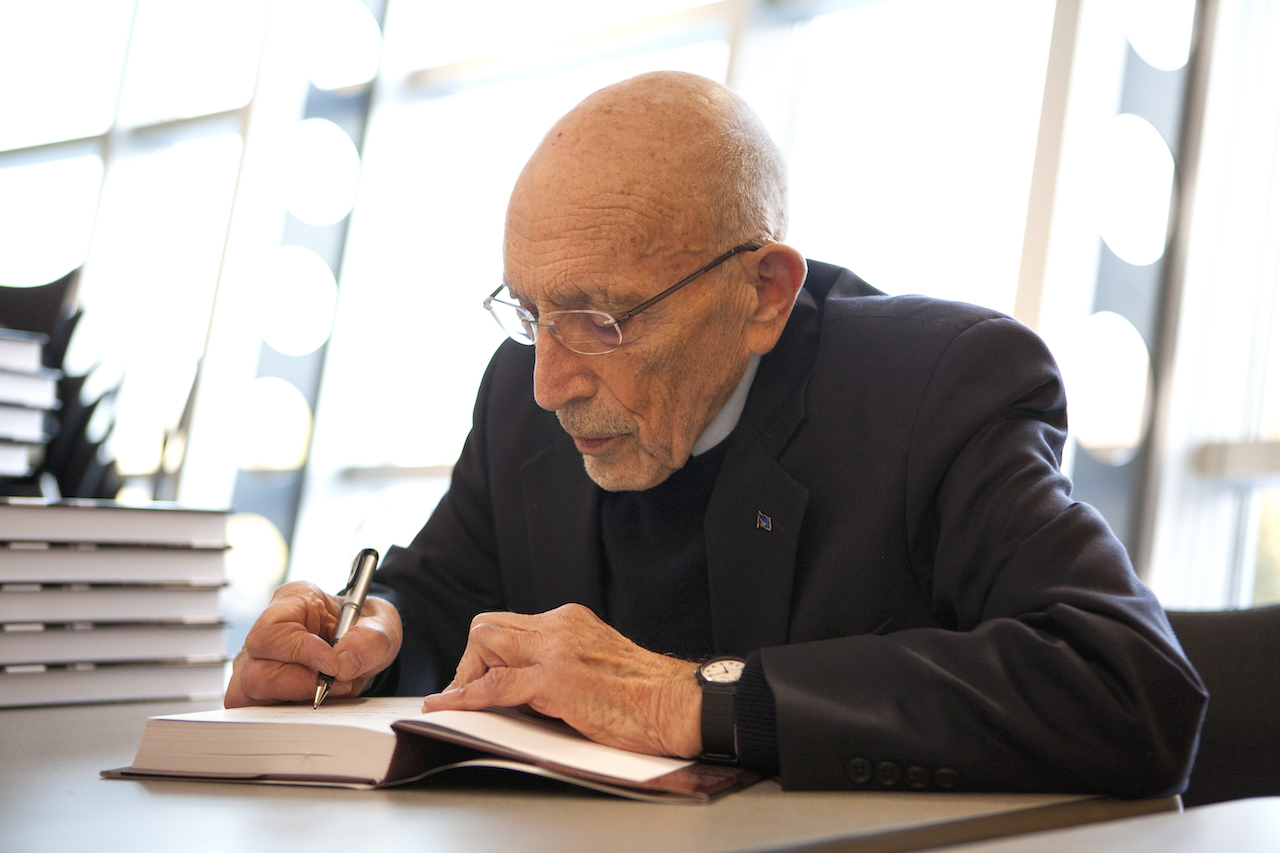

New documentary film features ISER’s prominent first director

by Catalina Myers | June 2022

“Even as a kid, I liked to have a garden and grow things — it’s really fun to watch things grow,” said Vic Fischer recently in the latest film in the Magnetic North documentary series produced by the Alaska Humanities Forum in partnership with the Rasmuson Foundation.

The series explores the lives of prominent Alaskans who have shaped the state’s history, values and spirit. While it is hard to distill 96 years of Fischer’s life into 25 minutes, the film offers a glimpse into the Institute of Social and Economic Research’s (ISER) first director, delegate to Alaska’s Constitutional Convention, state legislator and activist, and his enduring legacy of tireless advocacy for the preservation of the public good in Alaska.

Born in 1924 in Berlin, Germany, to a Russian mother and an American father, Fischer spent much of his early childhood in Moscow, Russia, before his family fled Stalin’s regime in 1939. Witnessing the “fall of democracy” in his youth impacted him for the rest of his life, pushing him into a life of public service.

Just one semester into his education at the University of Wisconsin, the United States entered World War II and Fischer, at 18 years old, enlisted in the U.S. Army. He promised himself that he would go West if he survived the war. Fischer liked to frequent the ship’s library and found a book about the Alaska territory during the journey across the Atlantic. After reading it from cover to cover, he knew he was destined for the union’s farthest northern and western territory.

As far west and as far north

Fischer arrived in Alaska in 1950 as a city planner, working on projects across the state. He immediately immersed himself in his community, culture and politics and has served the state in many capacities in the decades following. In 1966, Fischer was recruited to be the Institute of Social, Economic and Government Research (ISEGR), now known as ISER and commonly referred to as “the institute of everything.”

“Fischer shepherded ISER from a fledgling institute, from hiring the first researcher under himself to being this broad-based organization,” said Diane Hirshberg, current director of ISER and the institute’s 12th director. Not only has he mentored her throughout her career at UAA, but he became a close friend, officiating her wedding in 2006. “He had the smarts to recruit a whole group of brilliant people to become researchers and future directors like Lee Gorsuch, Gunnar Knapp, Scott Goldsmith and Matt Berman — this group of economists that really built ISER’s reputation.”

According to Fischer, that was the goal of ISER. To be an institute that served as a place to provide business leaders, government officials and policymakers a place to go when they had questions regarding economic, social and policy issues.

Like many leaders, Fischer was forward-thinking and creative, which allowed him to connect and network with people and easily move within political spheres from Alaska to Washington D.C. In 1966, Fischer finalized a grant proposal to the Ford Foundation and, in 1967, secured $550,000 — an unprecedented amount — to rapidly grow ISER to what it is today.

Fischer’s vision for ISER was to build an institute that addressed a number of social and economic issues from community development, Alaska Native leadership, health, education, natural resources, including petroleum, public finance, environmental development and many more topics.

Under Fischer’s leadership, ISER became the “institution of everything,” contributing to Alaska’s history and transformation from early statehood, through the boom of the pipeline years, to establishing connections between researchers and scientific academies in the Russia Far East, to modern times, and the institute’s current collaborations with researchers from across the Arctic and Circumpolar North. Although Fischer officially retired from ISER in 1976, he has remained involved with the institute since its founding. In 1996, the University of Alaska System awarded him the status of Director Emeritus, and, in 2006, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws from UAA.

A little bit of everything

Fischer is now in his mid-90s and is just as involved in the state as when he arrived. Fischer’s life almost plays out like an epic movie but is a reminder that one person can significantly impact the people, place and community they choose to live.

“Vic cares deeply about the people around him,” Hirshberg said. “He is a generous, loving, caring person that cares deeply about the state. There’s no question that Alaska is important to him.”

Fischer’s legacy in Alaska will continue to live on in the policies and legislation he helped create, the cities he designed and planned and the powerhouse academic institution he helped build from the ground up. For Fischer, Alaska’s vast and wild landscape was a garden for him to plant seeds for a future that brought the people, culture and communities of the state he so deeply loved together.