Big States, Tiny Research

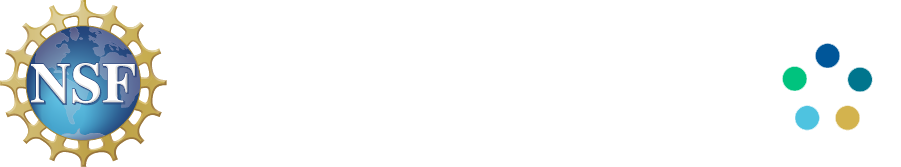

Boise State University Ph.D student Jessica Bernardin works on culturing microbes in Mario Muscarella’s lab in the UAF West Ridge Research Building.

Alaska can’t offer much in the way of sagebrush or pygmy rabbits. What it does have is burgeoning capacity to study microbes, which is why a consortium of Western EPSCoR states is partnering with UAF on a study of how the gut bacteria of desert animals enable them to digest toxic plants.

“It’s really trying to explore this arms race between plants and the defensive compounds they make and their consumers, meaning animals,” said Mario Muscarella, an Assistant Professor of Microbiology at UAF and the main Alaska partner in the enterprise. “The part of the project that I contribute to is thinking about how the gut microbiome helps animals detoxify the plant compounds.”

Muscarella is the newest partner in “Genomics Underlying Toxin Tolerance (GUTT)”, an EPSCoR Track-2 project that began in 2018 with the goal of better understanding the relationship between toxic plants and herbivores. Campuses in Idaho, Nevada and Wyoming have been collaborating on the $7 million project, which to this point has mainly focused on the toxic plant sagebrush and three animals that can digest it: Greater sage-grouse, pygmy rabbits, and wood rats. “These are plants that not a lot of animals can eat, but these animals rely on them, especially during certain times of year when it’s snowy,” noted Stephanie Galla, a postdoctoral researcher at Boise State University working on the effort.

The sprawling GUTT project tackles plant-animal interactions from a number of different angles – an approach the research team calls “culture-omics” - and now involves researchers from six different campuses. Muscarella said he got involved in the project last year when project lead Jennifer Forbey of Boise State approached him about injecting his own techniques, which entail culturing gut microbes and studying them through the lenses of physiology and genomics.

UAF Assistant Professor of Microbiology Mario Muscarella and Boise State University Ph.D student Jessica Bernardin after concluding research in Muscarella’s lab in the UAF West Ridge Research Building.

“Mario’s coming in with a lot of skillsets for culturing that we wouldn’t necessarily have at Boise State,” said Galla, who visited Muscarella’s lab in late January along with Boise State grad student Jessica Bernardin. “There are a lot of tools here where you’re able to culture and measure the physiology - not just understand the genetics, but what the microbes are actually doing.” She also noted another allure of UAF is its infrastructure for culturing and preserving specimens, including both excellent lab facilities and expansive liquid nitrogen tanks at the UA Museum of the North.

Galla and Bernardin spent much of their recent visit learning culturing techniques at Muscarella’s West Ridge Research Building lab. But they also had another goal: there are plans to expand the study to some Alaska fauna, such as wood rats from Southeast and ptarmigan and moose in the Interior. So the two visitors ventured out onto the North Campus Trails to (easily) locate some droppings from the latter, which they are experimenting with storing in various media. “I like to tell people we really leverage the power of poop in our work,” Galla noted. “So we collect fecal samples from a lot of our organisms, and that is being used as a proxy to understand what’s in the gut.”

UAF Research Professional Amanda Stromecki and Boise State University postdoctoral researcher Stephanie Galla collect moose droppings on the UAF North Campus trails.

The project is slated to continue through September 2023. Muscarella has already hired a research professional to help with the project and plans undergraduate summer hires, and the project will also enable him to enhance the research content of his undergraduate microbiology course. Future research visits are planned to and from the other states working on the project, and Institute of Arctic Biology researchers led by Knut Kielland and Link Olson are also developing plans to extend the project to the aforementioned Alaskan flora.

Muscarella is excited about the project’s potential for advancing basic science, and both he and Galla suggested practical applications for the work as well. Galla noted the research will be useful to land managers working on potentially reseeding areas with sagebrush or translocating animals to bolster their populations. And Muscarella said the findings have potential medical and pharmaceutical applications as well.

“(An animal gut biome) might produce chemical x and that might reduce inflammation when they consume a toxic compound,” he noted, “and now we know about that molecule and the organisms that produce it, and we could potentially use that in an applied setting.”

For more information about the project please visit the GUTT website.