Forward of "Tales of Ticasuk" - Part 2

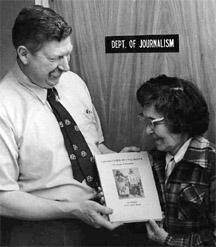

Her many projects were carried out in spite of difficult battles with tuberculosis, cancer, cataracts and other health problems. She continued to earn degrees. In 1973 she completed the Master of Arts degree in communication arts. In 1980 she graduated again, with a Bachelor of Arts in Inupiaq Eskimo, then enrolled again to begin work on a Ph.D.

Eventually, her poor health began to catch up with her. A year before she died, a doctor predicted she would not survive more than three months—but he didn't tell Emily.

She said at the time of her return from the intensive care unit that "I've been cured." Whether she was cured or not, there seemed to be some kind of remission of the cancer and by August she was ready for another year of school. When I went to Unalakleet to visit her that month, she asked me, "When does school start?"

After learning the dates, she asked, "When is our weekly conference?"

"Conference?" I asked. "I've retired, Emily. This was my last year of teaching. I'm back working as a journalist again."

"Retired! You're too young to retire. Even if you retire from the university, you can't retire from the book publishing ventures we've been working on. Now tell me, when will we have our weekly conference?"

"Well," I said, resignedly, "let me see your course schedule after you are enrolled and we'll work out a suitable time."

Although she was very tired from her long struggle just to stay alive and she sometimes needed blood transfusions to give her strength, she continued to move about campus, though ever so slowly now, moving ahead on her manuscripts in spite of eyes that were so weak that reading was nearly impossible. In December, there was some improvement in her eyes after a cataract operation on one eye and a laser operation on the other, but her general condition was deteriorating.

On April 15, after a two-week rest at Unalakleet with her oldest son, Leonard, and his family, Emily returned to Fairbanks Memorial Hospital. When I stopped in to see her a few days later, Emily was resigned: "I'm not going to make it this time," she said. "Let's get busy. We have much to do before I go. First off, I've got to get new glasses so I can read. Will you take me to the doctor tomorrow?"

Deeply religious, Emily had long ago made peace with her God. When I took her in a wheelchair to the doctor, her mind was racing through images of work that needed to be done, vacation plans she knew would never be carried out, and her imminent death. "Don't cry at my funeral," she said. "It should be a happy time because I'm going to be with the Lord."

After a brief pause, she began to talk about summer plans and asked me to come to Unalakleet in early June to photograph several plants for a section of the Eskimo encyclopedia she was planning. "My niece and I are going to set up a big tent at Unalakleet, over by the trees, but away from the bears. We'll put it where we can hear the birds singing in the morning. My niece will cut the wood and do the heavy work and I'll do the cooking."

A week later she was sinking fast. She whispered to me " I'm going to Heaven." Five days later she was gone. She would not live to receive her doctorate.

"I am overwhelmed!" She had written to Chancellor Patrick O'Rourke, upon receiving notice she would become an honorary doctor of humanities. "This news has uplifted my spirits, especially to try to continue to live to complete the work on the Eskimo encyclopedia and to promote building a multicultural center on the Farbanks campus."

Son Mevin Brown, a 1967 graduate of the university, accepted the doctorate for her on May 9. Although Emily didn't live to see all her goals accomplished, she died knowing that others would carry on her work.