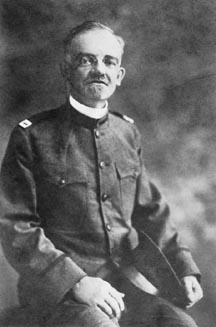

Alfred Brooks

Alfred Brooks was a geologist who traveled thousands of miles in Alaska and left his

name on the state’s northernmost mountain range. Twenty years before his death in

1924, he also left behind a summary of what Alaska was like one century ago, when

“large areas (were) still practically unexplored.”

To see what Brooks had to say about the Alaska of 1906, I pulled a copy of his “Geography

and Geology of Alaska: A Summary of Existing Knowledge” from a shelf of rare books

in the Keith B. Mather Library, part of the University of Alaska’s Geophysical Institute and International Arctic

Research Center.

In his government report, Brooks pointed out misconceptions about Alaska that endure

today. He wrote in his introduction:

“If facts are presented which may seem elementary, it is because even well-informed

people have been known to harbor misconceptions in regard to the orographic features,

climate, and general character of Alaska. Those who read about the perils and privations

of winter travel and explorations are apt to picture a region of ice and snow; others,

again, who have personal knowledge of the tourist route of southeastern Alaska, regard

the whole district as one of rugged mountains and glaciers.”

In Brooks’ day, about 60,000 people lived in Alaska, yet they were scattered wider

across the territory than people are today. The Klondike gold rush and the stampedes

that followed had driven determined men to the far corners of Alaska.

“The more venturous prospector found no risk too hazardous, no difficulty too great,

and now there is hardly a stream which has not been panned by him, and hardly a forest

which has not resounded to the blows of his ax,” Brooks wrote. “Evidences of his presence

are to be found from the almost tropical jungles of southeastern Alaska to the barren

grounds of the north which skirt the Arctic Ocean.

While today’s scientists can sometimes use satellites to gain information about Alaska

without leaving their offices, Brooks and his contemporaries at the U.S. Geological

Survey spent their entire summers on traverses of Alaska at the turn of the century.

They performed their work without the help of the airplane, which had not yet been

invented, nor the internal combustion engine.

Brooks wrote of an 1899 expedition he made with topographer William Peters to map

the country from Lynn Canal near Haines west through the mountains of the St. Elias

Range and northward through what is today Wrangell St. Elias National Park. They filled

in a void in Alaska’s map until they reached the settlement of Fortymile on the Yukon

River.

“The journey was made with horses, with only five out of the original 15 reaching

the Yukon,” Brooks wrote.

By 1904, USGS scientists mapped one-fifth of Alaska, following rivers and trekking

overland when they could. Brooks attributed the agency’s success to its ability to

choose adventurers.

“Of the twenty or more parties which the Geological Survey has sent to Alaska, hardly

a single one has failed to execute the work allotted to it,” Brooks wrote. “This is

largely because those who were entrusted with their leadership were specially fitted,

by nature as well as by experience and training, for the undertaking. The parties

have usually been made up of a few carefully chosen men, and the physical work and

discomforts, as well as hardships, have been shared by leaders and men alike.”

Brooks, who later wrote about his personal experiences in Alaska, concluded his section

on exploration in “Geography and Geology of Alaska” by addressing critics of government

spending who had no idea of the hazards and difficulty of travel in Alaska.

“Alaskan surveys and explorations have never been and never will be easy,” Brooks

wrote. “Throughout its history, the geographic investigation has been a tale of hardship

and suffering and not infrequently of death. Let those who are not personally familiar

with the character of the difficulties not judge it too harshly.”

UA Site named after Alfred Brooks

Link

Brooks Memorial Mines Building Dedication Ceremonies Held (1952)